|

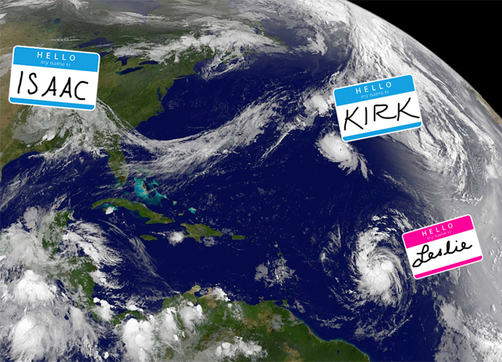

by Aisha Keown-Lang '18  Kirk's a jerk, but Leslie wears stilettos fora reason. [image via] Storm Juno, named after the Roman goddess of love, was pretty fun — students across the East Coast enjoyed cancelled classes and an impromptu pajama day. Juno was an example of a storm gone “right” — that is to say, it was underwhelming. While the Weather Channel and media promised us the “blizzard of the century,” those of us who ventured outside know that it was just some heavy snow and a few gusty winds. How much did you prepare for Storm Juno? If you are like most people, you bought a few extra snacks and bunkered down inside to avoid the cold. Deciding how much to prepare for any natural disaster is a serious issue; during Hurricane Katrina, as with other storms, many deaths were the result of a lack of preparedness. The reason for this lack of preparation, however, may surprise you. A study published in 2014 garnered substantial media coverage with its claim that female-named hurricanes are more deadly than male-named hurricanes because sexist biases lead them to believe female hurricanes are less dangerous. As a result, people tend to prepare less for storms with female names, which can have deadly consequences. The study, lead by Kiju Jung at the University of Illinois, used statistical analysis to compare the death rates for female and male hurricanes and concluded that female hurricanes cause three times as many deaths. A difference in death rates could have important policy implications for safety organizations, such as the National Weather Service (NWS).

If people really do react differently to differently named storms and hurricanes, then it would be in the NWS’s interest to begin strategically naming its hurricanes to encourage the correct level of preparedness. There has, however, been major opposition to this study. The first major claim against the study is that from 1953 to 1978, hurricanes had exclusively female names. Thus, female hurricanes are automatically going to be responsible for more deaths than male hurricanes. Several scientists, such as Jeff Lazo of the National Centre for Atmospheric Research, think that the model used by Jung should have better accounted for this inherent bias. In response to this criticism, Jung and his team claim that they factored in the pre-male named hurricanes because in addition to categorizing names as being “male” or “female,” they categorized the female hurricane names as being “more feminine” and “less feminine” and included this as a factor in their analysis. The authors claim that even when you compare the “more feminine” and “less feminine” groups, the “more feminine” hurricanes have higher death rates. There are other critical issues with the study. For example, the team included “indirect deaths”, or deaths that occur from things such as branches and telephone wires that fall after the storm, These deaths are unrelated to people’s preparedness and thus are confounding the data. Another problem with including “indirect deaths” is that infrastructure has improved since the years when hurricanes only had female names, yet another factor muddling the data. In the face of all this criticism, Jung and his team maintain that their study was accurate. The idea of social biases influencing our behavior subconsciously is not an unfamiliar or inaccurate one, but while Jung’s theory is within the realm of possibility, at this point, it lacks definitive proof. Regardless, as global climate change brings about more extreme weather patterns, public safety should not be taken lightly. In the meantime, however, we can all do our best to remind ourselves not to underestimate the power of a name.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |