by Hallee Foster '15 Former-49ers Quarterback, Alex Smith, bears a brutal sack to the head. [image via] Three-letter acronyms abound in our society – NRA, NBA, CDC – and often name agencies that seldom interact. However, an unlikely friendship has recently formed between two three-letter permutations that seem to occupy opposite sides of the spectrum: NFL and NIH. In 2012, the NFL – yes, the National Football League – donated a whopping $30 million to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health to fund research on traumatic brain injury – a subject that hits close to home for the NFL and its players.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a serious public health problem with an ever-widening scope of severity. It is currently the number one cause of death amongst young adults [1] and is a particular menace to young athletes. Perhaps even more frightening than its prevalence is its nebulosity. We have no rapid, reliable diagnostic methods for concussions and know little about the long-term consequences of repetitive insult to the head other than the high risk of developing progressive brain degeneration, chronic traumatic encephalography (CTE). Brains afflicted by CTE show demonstrable physical damage, including excess protein build up and tangled cells. CTE produces symptoms analogous to those of Alzheimer’s – irritability, confusion, depression, mood swings, memory loss, and cognitive difficulties. Preliminary tests have revealed that several former high-profile athletes, including Hall of Fame running back, Tony Dorsett, may be living with CTE. Fifty-four former-NFL players have donated their brains for scientific analysis post-mortem to the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University. Fifty-two of said brains show marked signs of brain damage from repeated concussions [2].

0 Comments

by Denise Croote '16 This three-minute clip tells the timeless tale of predator and prey, of a bright-eyed and bushy tailed young squirrel eager to take on the world and a particularly malicious hawk hungry for lunch. In a way, we were all bright-eyed, bushy tailed squirrels simply trying to enjoy the Brown experience, until all of these midterms just before Spring Break tried to eat us. Nevertheless, survive we must and prevail we shall. If you've ever wondered about the facial expressions of a squirrel as a hawk is shaking it from a tree, this video has your answer. If you could care less about a hawk-squirrel hunt, this video will still astound you with its HD 1080p resolution. How this was caught on film is a complete mystery. Good luck, fellow squirrels! (If you're a hawk, well, good luck to you too, but please don't eat me.) by Ben Williams '16  "Sometimes it's said that psychiatrists "Sometimes it's said that psychiatristsare doctors who are frightened by the sight of blood. I might have fallen into that category." [image via] When asked how he remains sane while studying the psychological effects of harrowing experiences, renowned psychiatrist and author Robert J. Lifton replies, "I draw bird cartoons." "We need a sense of absurdity, sometimes gallows humor, to survive the absurdities of our world," said Dr. Lifton in a speech entitled "Research as Witness: A Psychiatrist’s Struggles with Extreme Events," delivered at Brown on October 21, 2013 as the 21st annual Harriet W. Sheridan Literature and Medicine Lecture. The 87-year-old Brooklyn native has held positions at Harvard, Yale, and the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He has published over 20 books on the psychological consequences of historical events. Over the course of his career, Lifton has interviewed American prisoners of war, survivors of Hiroshima, and Nazi doctors. After two years in the Air Force in Korea and Japan, Lifton embarked on the "struggle to bring together psychology and history." Eschewing the ideally objective approach of scientific research, Dr. Lifton found himself constantly motivated by ethical concerns and a desire to participate in what he calls "relevant activism."  NASA provides a recipe for El Niño pudding! NASA provides a recipe for El Niño pudding! by Sarah Blunt ‘17 Eavesdropping on my classmates’ conversations around campus on a particularly cold day a few weeks ago (all in the name of science), I was surprised to hear the words “El Niño,” and “global warming” almost as often as “cold,” “brr,” and “polar vortex.” I remembered learning about El Niño in high school, but I couldn’t see how it related to global warming, if at all. I decided to do some digging, to inform the population of Brunonia once and for all about what El Niño is, how it’s measured, and how it relates to global warming. El Niño is a result of the continuous exchange of water between the Earth’s atmosphere and its largest ocean, the Pacific. (It’s just a large-scale water cycle). Periodic disruptions in this cycle that stem from massive, planet-traversing ocean waves cause pressure differences between the ocean and the water-vapor-filled atmosphere. These differences are cyclical, just like the massive waves that cause them, and therefore have both high and low pressure extremes. El Niño occurs when the difference between the pressures of the atmosphere and the Pacific is lowest, and is characterized by increased precipitation and higher temperatures in equatorial regions of the Earth. Since the Earth’s atmosphere flows (it’s a fluid, after all, mostly made up of water vapor), these El Niño conditions can have far-reaching effects all around the globe [1]. In Rhode Island, for example, the average temperature during an El Niño year is almost 2 degrees hotter than during a normal year! [2] by Kevin Tang '17  For the past few years, mobile networks have been increasingly pushing their “innovative” and “lightning-fast” 4G networks, each laying its own claim to having the fastest speeds or greatest coverage. But what exactly is this 4G that everyone is so hyped up about? Ask the average person on the street, and chances are that they won’t know many details at all. Apart from the logical fact that 4G stands for “fourth generation” and is supposedly markedly faster than 3G speeds, most of the general public would not normally dig much deeper than that. In all fairness, the 4G concept is complicated. Although networks such as LTE are edging closer and closer to becoming veritable broadband 4G networks, much of the marketing one may see on television or internet marketing ads are just that: marketing, and does not necessarily refer to a true 4G network. by Nari Lee '17  Sex differences can create problems both in pain and its treatment. This topic adds yet another aspect to today’s complex sex/gender equality debate, but it’s highly relevant for anyone who experiences pain – namely, everyone. Research has revealed that males and females perceive pain differently, yet management of pain for men and women doesn't take that into account. In fact, treatment of pain is often generalized for both sexes (or worse, biased). Instead, doctors should tailor treatments to the differences in female and male bodies’ responses to pain and pain medicine. To do this, though, greater research is needed on sex-specific responses to pain treatments. by Haily Tran '16

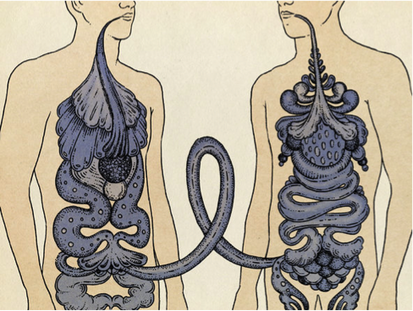

"This spring I saved a friend from a terrible illness, maybe even death. No, I didn’t donate a kidney or a piece of my lung. I did it with my stool." [image via]

We’re all familiar with the fibrous substance our bodies excrete on a regular basis. You probably don’t think twice about flushing it down the toilet. But, here’s a thought: human fecal matter has been used in more than 3,000 medical procedures around the world to cure various gastrointestinal illnesses. (1)

Our digestive system is home to over 20,000 different species of good bacteria, most of which accompany our digested food waste out of the body (2). A sample of healthy human feces is the densest bacterial ecosystem in nature—trillions of strains versus the mere 30 found in the best probiotics (3). Fecal microbiota is a burgeoning field of research as more scientists look to Mother Nature for ingenious medical solutions rather than synthesizing them in a lab. by Katie Han '17

Don't you just love the solar system? [image via]

Space is fascinating. Every child is bound to fall in love with the idea of flying on a sleek rocket to journey away from Earth. And at at least one reflective point as a teenager, that child will probably ponder the insignificance of human beings in this vast, endless universe filled with myriads of galaxies and will realize that we are essentially “specks.” Inspired by this sense of wonder, some will carry this passion into their careers, traveling out to space themselves, or building rockets and robots that do so.

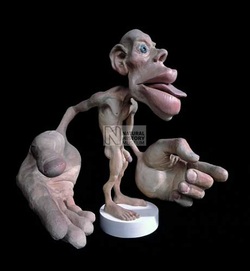

One of the leading space agencies in the world, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) currently has over 150 missions that range from monitoring Earth via satellites, sending humans to space, studying other planets in the solar system, and exploring the universe. The technology for launching rockets is developing dramatically over the years, yet sharing of such information between countries has always been sensitive. Affluent, developed countries often join the competitive “space race” to show off their scientific advancement, while the unspoken race for power has aroused a deep fear of application of this knowledge for military purposes. by Noah Schlottman '16  Healthy munchie alternatives? [image via] Healthy munchie alternatives? [image via] It is something that has, most likely, perplexed humanity for thousands of years (1). It is something that has probably confused recreational users, the shamans who were its prescribers, and maybe even Shakespeare (2). Certainly there are Brown students who have pondered time and again, perhaps at various times throughout this university’s 250 years: Why does marijuana give you the munchies? Though we haven’t figured out the full answer yet, a group of researchers at the University of Bordeaux conducted a study that gives us some insight into why, indeed, marijuana makes people hungry (3). Tetrahydrocannabinol (commonly known as THC) is the “active ingredient” in cannabis. It mimics the activity of chemicals called cannabinoids that are naturally produced by our brains. These chemicals fit into receptors in the endocannabinoid system, which is involved in controlling mood, memory, pain, and—most importantly in this case—appetite. An ingenious experimental design allowed them to focus on certain cannabinoid receptors in mice’s olfactory bulbs, a part of the brain involved in odor perception. A Review of The Mystery Of The Mind By Wilder Penfield by Matthew Lee '15  "Hi, do you want a massage?" [image via] "Hi, do you want a massage?" [image via] Find this book in the Sci Li! Paperback: 152 pages Publisher: Princeton University (March 1978) ISBN-13: 978-0691023601 Anyone who has taken Neuro 1 will recognize the somatosensory homunculus, the funny looking guy with giant hands, puffy lips, and an emaciated body. The homunculus is based on a map of the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), and the size of each body part corresponds to the amount of brain that responds to a touch of that body part. Our brains devote the most processing power to understanding what our hands touch, so the homunculus’ hands are disproportionately large.  [image via] [image via] Dr. Wilder Penfield (1891-1976), an eminent Canadian neurosurgeon, provided the scientific evidence that evolved into the homunculus. He mapped out which parts of the brain are associated with which body parts by sticking an electrode into a patient’s brain, zapping it, and then asking the patient which part of their body had responded. Penfield also used electrical stimulation to investigate the relationship between the mind and the brain: does the mind arise from the brain, or are they separate entities? In The Mystery of the Mind, he considers the evidence he has collected from patients with epilepsy, who so graciously allowed him to poke and zap their brains. |