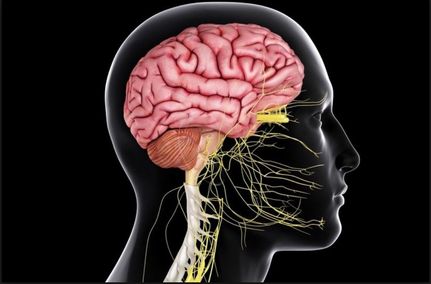

Image of the Central Nervous System. https://www.thoughtco.com/central-nervous-system-373578 Image of the Central Nervous System. https://www.thoughtco.com/central-nervous-system-373578 By Emily Rehmet, '20 For years, the American Psychological Association has classified eating disorders into a discrete category on its own, a direct byproduct of patients having doubts about their body size and image. However, a recent study suggests that bulimia nervosa may be connected to something deeper… a vehicle for people to escape from self-critical thoughts. New research has shown that rather than simply having an obsession with food, women with this disorder have decreased blood flow to a brain area associated with self reflection and self worth. What is this newly discovered brain area that could be causing this you may ask? A region called the precuneus [1]. Previous research has determined that bulimia nervosa, a prevalent mental disorder characterized by binge eating and purging, most prevalent in adolescent females, is associated with increased negative emotions. According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, nearly half of bulimia patients have comorbid (or co-occurring) mood disorders, and more than half of these patients have comorbid anxiety disorders [2]. However, few studies have delved into what part of the brain could be contributing to this life-threatening disorder and feelings of self-negativity. A new study in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology proposes that the precuneus, a region associated with self-reflection and mental representations of the self, could serve as the neurobiological basis for escape theories of emotion regulation in this eating disorder [1]. The study sought to provoke a stress response in women with bulimia nervosa, and then afterwards examine the neurobiological response to food cues by looking at their brain activity. In the first study, 10 women diagnosed with DSM-5 bulimia nervosa and 10 women without the disorder viewed a number of neutral cues followed by highly palatable food cues. Then, they solved challenging arithmetic problems (to produce failure), reported their low accuracy to a research team audience, and then again viewed a number of neutral cues followed by highly palatable food cues. When comparing the fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) brain scans of patients with the eating disorder versus ones without the disorder after the stressful event, it was seen that those with the disorder had significantly decreased activation in the right and left precuneus, left cuneus and right anterior vermis, while the healthy patients demonstrated increased activation in these same areas. In a follow-up study almost identical to the first, women with bulimia nervosa had decreased activation to food cues in the right cerebellum, right and left paracingulate gyrus, and left precuneus after a stressful situation. The conclusion that there is hypoactivation in the precuneus area of the brain in bulimia patients and hyperactivation in healthy patients is consistent with the characterization of binge eating as an escape from self-awareness, a notion originally proposed by Heatherton and Baumeister (1991). These results are critical in understanding a life-threatening disease targeting young women and girls, and are the first to provide a neural basis for understanding what the disorder is really all about. As lead author Brittany Collins Ph.D. of the National Medical Center says, “To our knowledge, the current study is the first investigation of the neural reactions to food cues following a stressful event in women with bulimia nervosa" [3]. Understanding the root of the problem, maybe we will soon be able to develop treatments to increase activity in this area of the brain. After all, eating, drinking, and sleeping are the basis of human existence, and as co-editors Pamela Keel Ph.D. Florida State University and Gregory Smith Ph.D. University of Kentucky write, such a disorder perpetuates “dysfunction related to the basic need of food consumption.” [1] Collins, B., Breithaupt, L., McDowell, J. E., Miller, L. S., Thompson, J., & Fischer, S. (2017). The impact of acute stress on the neural processing of food cues in bulimia nervosa: Replication in two samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(5), 540-551. Available at: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/abn-abn0000242.pdf [2] “Eating Disorder Statistics; National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders.” National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, www.anad.org/get-information/about-eating-disorders/eating-disorders-statistics/. [3] “Under Stress, Brains of Bulimics Respond Differently to Food.” American Psychological Association, American Psychological Association, 10 July 2017. Available at: www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/07/stress-brains.aspx. Emily RehmetEmily is a Bachelor of Arts Candidate in the Cognitive Neuroscience and Public Policy Departments at Brown University. She is interested in the intersection between neuroscience, women's health, and criminal justice reform.

1 Comment

|