|

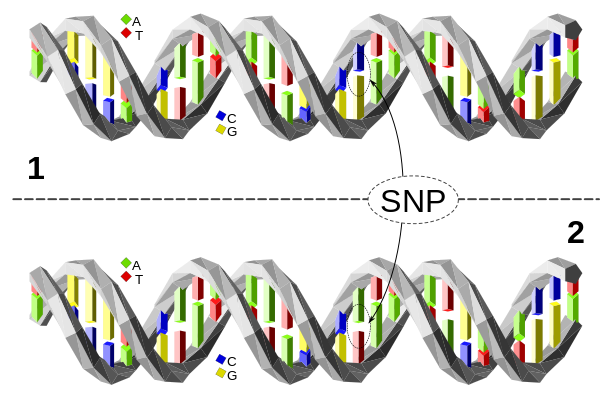

Written by: Shreya Rajachandran '22 Edited by: Carlie Darefsky '22 When we do a Google search for “Vikings”, what do we see? Typically, tall blonde men with horned helmets, wielding double-sided axes as they traverse Europe in their fleets of ships and raid countrysides in search of riches. Modern depictions paint Viking life as a monoculture, and we consequently tend to think of Vikings as warlike people who terrorized Europe from the 9th to the 11th century (1). However, a newly published study involving the largest survey of Viking DNA to-date aims to turn this stereotype on its head. Published on September 16, 2020, the paper “Population genomics of the Viking world” by Margaryan et al. uses ancient DNA analysis to provide a new perspective on Viking culture and society in the medieval period. Researchers surveyed DNA from 442 known Viking graves from all over Europe— an accomplishment which took six years to complete (2). Although the archaeological sites surveyed ranged from 2400 BC to 1600 AD, the graves still contained traces of DNA. To analyze the genetic material of these graves, the researchers turned to the shotgun sequencing method of analysis: a process that allowed researchers to sequence long strands of DNA efficiently. To do this, an unknown DNA strand is broken down into small pieces, which are then sequenced individually. Those small fragments are then analyzed by a computer program, which puts the small fragments in their correct order based on overlapping sequences, allowing investigators to visualize the sequence of the original DNA (3). After they had sequenced the DNA, researchers were able to compare various genes found in the ancient Viking DNA to the DNA of European populations, resulting in some surprising findings (2). Although Vikings are well known as maritime travelers, this study found significant genetic diversity in Viking DNA within Scandinavia, finding evidence for a greater Viking presence within Denmark, Sweden, and the wider Baltic Sea. This diversity extends to the contents of the graves themselves; within the graves researchers found non-Scandinavian DNA, indicating that non-Scandinavian ethnic groups were integrated into Viking culture. By analyzing the similarity of DNA amongst mass Viking graves, the authors also discovered that Viking raids were typically a family affair, involving close relatives rather than a random assemblage of warriors (2). DNA also proved useful in tracking single genes through Viking and modern European populations. The group isolated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), changes in single DNA bases that can alter the expression of specific genes. To be considered SNPs, these mutations have to be present in a significant part of the population, making them ideal for tracing the expression of genes throughout history (4). Through this process, researchers could compare the genes of Viking graves to modern northern European DNA, looking for common SNPs. Specifically, the researchers looked at hair color and lactose tolerance. They found that most Vikings had a high probability of having black hair, and had increased lactose tolerance compared to their ancestors, likely a result of intermarriage with mainland European populations (2). So, what does all this mean, and why do we care? For years, historians have argued that the Vikings were actually a diverse group of individuals, who, because of their roots in maritime trade and raiding, settled all over Europe. Through ancient DNA analysis, this paper helps to confirm that theory. In this vein, this paper also deconstructs the idea of the Vikings as a violent race, incapable of assimilation and coexistence with local societies by highlighting the substantial non-Scandanavian ancestry of Viking Age individuals (2). Most importantly, however, these findings are a critical reminder of the increasing intersections between historical research and the scientific method and underscore the value of pairing these two approaches to understand ancient societies. Works Cited: 1. Gorman J. The Vikings Were More Complicated Than You Might Think [Internet]. The New York Times. The New York Times; 2020 [cited 2020Oct8]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/16/science/vikings-DNA.html 2. Margaryan A, Lawson DJ, Sikora M, Racimo F, Rasmussen S, Moltke I, et al. Population genomics of the Viking world. Nature. 2020 Sep 17;585(7825):390–6. [Image Citation] The Funeral of a Viking | Art UK [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 25]. Available from: https://artuk.org/shop/image-library/gallery-product/poster/the-funeral-of-a-viking-204862/posterid/204862.html [Image Citation] Shotgun Sequencing [Internet]. Genome.gov. [cited 2020 Oct 16]. Available from: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Shotgun-Sequencing [Image Citation] Single-nucleotide polymorphism - Wikipedia [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 25]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single-nucleotide_polymorphism

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |