|

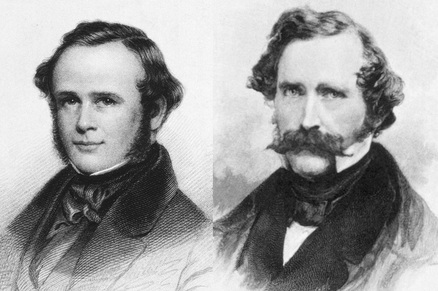

as a pain reliever. [image via] by Sophia Park '13.5 Pain is perhaps our most important sense for survival – it warns us with a piercing signal that our body has sustained damage. However, it is unpleasant by nature. The search to relieve pain dates back to at least 3400 BC, when ancient Sumerians used opium (1). In modern times, with advances in science and technology, we have a much more diverse and refined list of chemical agents for various medical purposes. The advent of inhalant anesthesia contributed immensely to the development of modern general anesthesia. Currently, the most commonly used inhalational anesthetic agents are isoflurane, desflurane, sevoflurane, and nitrous oxide. When the idea of inhalational anesthesia first began to emerge, scientists focused on nitrous oxide and ether gas, largely due to their familiarity to people. Both gases were well known for their hypnotic effect. Nitrous oxide is also known as “laughing gas,” and was used recreationally to induce euphoria often accompanied by giggling, primarily at parties and in traveling shows (2, 3). An American dentist named Horace Wells (1815-1848) saw a “laughing gas” show and observed that a person who inhaled the gas did not sense pain while bumping into objects. Inspired, he applied it to his clinical practice, and observed that his patients did not feel pain during tooth extraction (4). Wells soon consulted William T. G. Morton (1819-1868), his former student who was studying at Harvard Medical School at the time. In 1845, Wells gave a demonstration of nitrous oxide at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston in the hall now named the Ether Dome. Unfortunately, his experiment failed: the patient screamed in pain as his tooth was extracted. Retrospectively, the amount of gas was insufficient for the patient and was removed too soon (4, 5). Ignorant of nitrous oxide’s weight-dependent dosage, the scholars at the demonstration discredited Wells for his groundless suggestion. Meanwhile, Morton remained inspired by Well’s initial idea. With advice from his professor Charles T. Jackson (1805-1880), he began his investigations on ether gas, whose anesthetic effect was relatively well-known at the time. He experimented with ether analgesia on his patients and recorded repeated successes (4). Morton was a guy with ambition who actively pursued fame and profit. Only two weeks after his initial success, he held a public demonstration at Mass General in 1846. It succeeded, and the news rapidly spread, gaining Morton fame as the first to use ether gas as an analgesic, or painkiller. However, his ambition blinded him. Because the effects of ether were well-known, he referred to his substance as “Letheon,” and hid its identity by adding aromatic oils in order to secure a patent (4).

The inhaler Morton used for "Letheon." [image via]

Meanwhile, Wells was experimenting with nitrous oxide, and he published his successes to academia. However, his once-lost credit could not be recovered. Traumatized, he began experimenting with chloroform on his own body. Ultimately, he became addicted, gradually lost sanity, and his life was never stable again.

Out of frustration, Wells made a tragic decision. On the morning of January 24, 1848, police found him on a street in New York, lying dead on the ground. With a chloroform soaked towel around his hat, he had committed suicide by cutting an artery in his left leg - at the age of 33 (4). At the same time, Morton’s life was also going downhill, as his profit-seeking began to create noise in the medical community. People began to notice that the self-declared new agent was in fact ether. Others claimed that they had used ether as an analgesic before Morton. First, Charles Jackson stepped in and argued that he had originally come up with the idea. This ignited a dispute with Morton that spanned almost 16 years. Adding to the complication, Crawford Long (1815-1878) from Georgia and William Clarke (1819-1898) from Rochester had been using ether for anesthesia since 1842, further weakening Morton’s stance (4). Driven into a corner, Morton applied to Congress for the recompense and sued the U.S. government, but the case ended without success due to insufficient evidence. The series of publicized disputes over patents and property only gained him notoriety for his inhumanity, and he was unable to recover his reputation before his death in 1868. Popular media often portray Morton as a man who lost philanthropic qualities that are essential as a health care provider in the face of fame and fortune. However, it is also true that the debate over the credit for the discovery itself seized the public’s attention and fueled further investigation in development of modern anesthetic methodologies. Although the competition among Wells, Morton, and Jackson drove their lives into tragedy, it is true that their discord and rivalry marked the development of modern anesthesia, which enabled the development of numerous modern surgical methods.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |