|

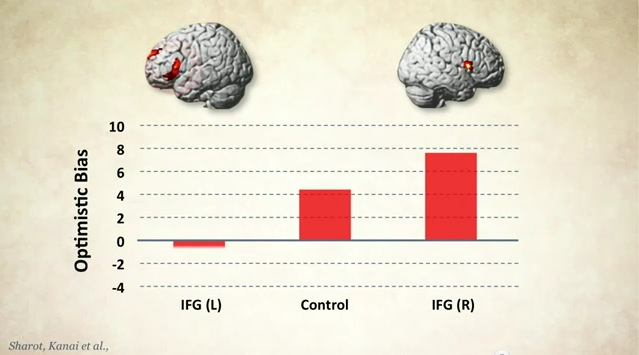

Written by: Esha Kataria ’24 Edited by: Madhu Subramanian ‘24 Living amidst a global pandemic, widespread civil unrest, and a polarizing election has been mentally and physically taxing. It is in these moments that I often ask myself: Is there a way out? How should I grapple with these uncertainties without losing my mind? From a young age, we've been told to always stay positive—to think on the bright side and see the glass as half full. But are our brains capable of being optimistic? Could it be the answer to our problems? These are the questions that scientists are attempting to answer. Scientists have multiple classifications for optimism. One such classification is dispositional optimism, in which being positive about daily events is seen as a personality trait. In the attributional style, optimists believe positive events are more consistent and frequent than negative events. Optimists see negative events as external and specific, and thus don’t assume blame for them. In another, “optimism bias,” the optimist believes that positive events are more likely to occur than negative events, causing them to underestimate risk [1]. There are key differences between optimists and pessimists. One such difference is their selection of where to focus their attention and how they process that information. Optimists tend to select positive cues from the environment, filtering out negative information. They believe they have the power to control the events that happen to them and interpret personal events differently, giving themselves credit for good events and assuming they will last [2]. Research indicates that optimistic thinking is associated with activity in the left hemisphere (LH) of the brain, which is responsible for maintaining physiological equilibrium. The right hemisphere (RH), on the other hand, is associated with the psychoneurological processes of pessimism. It functions as the brain’s alarm system, mediating stress and fear. Most of the time, these two hemispheres work together to create the way in which we view the world. In extreme situations, however, the contribution of one hemisphere can be amplified [2]. Neuroscientist Tali Sharot investigated optimism bias, “the belief that our future will be better than our past or present”, by scanning the brains of a study’s subjects using a functional MRI. Dr. Sharot specifically looked at the left inferior frontal gyrus, which is responsible for responding to positive news, and the right inferior frontal gyrus, which is responsible for responding to bad news. She found that the more optimistic you were, the less likely your right inferior frontal gyrus would respond to negative news. Furthermore when Dr. Sharot interfered with the participants’ right inferior frontal gyrus by passing a small magnetic pulse through their skull, their optimism bias increased. When she did the same to their left inferior frontal gyrus, their optimism bias completely disappeared and resembled pessimistic thinking. These results are illustrated in the graph below [3]. Though unrealistic optimism can lead to risk-taking behavior and faulty planning, Dr. Sharot explains that simply being aware of optimism bias can create a healthy balance. Being hopeful is equally important as optimism can carry multiple benefits [3]. For instance, optimism is correlated with increased well being and a better quality of life. In a study looking at the dispositional optimism and depression in victims of a natural disaster, research found that pessimists were at a greater risk of developing depression and anxiety. Optimists are better at coping with negative situations than pessimists, and are shown to use strategies aimed at reducing or managing their stressors with acceptance instead of avoiding them. This indirectly affects optimists’ quality of life, as it demonstrates a quicker recovery via adaptation. Beyond better mental health and quality of life, optimism has also been shown to improve physical health. Multiple studies have shown that increased dispositional optimism correlates with a lower probability of cardiovascular mortality amongst optimists [1]. Cancer patients were shown to have an increased survival period [1] and cardiovascular disease patients were less likely to require rehospitalization after surgery or experience cardiovascular death compared to pessimists [4]. Another study has shown that optimism is associated with a 11 to 15% longer life span amongst study participants [5]. Finally, optimism has been shown to lead to greater professional success, as it can inspire one to try harder and be more productive. In a Ted Talk “The happy secret to better work”, Shawn Anchor, former Professor of Positive Psychology, explains that our brains perform better when we are happier as it causes the release of the chemical dopamine, which activates the learning centers of our brain. This means we are more intelligent, creative, and productive when we are happy than when we feel neutral or unhappy. Anchor holds this to be the secret to success, stating that “90% of our long term happiness is determined by the way your brain processes the world” [6]. Clearly, there are multiple benefits to positive thinking. This leaves us with a question: how can we incorporate being optimistic into our daily lives? Some simple things we can do to foster optimism include cultivating gratitude by listing three things we are grateful for everyday, journaling about positive moments or visualizing your best self, exercise, mediation, and through random acts of kindness [6]. It is also important that we accept the inevitability of disappointments, become aware of when our brain spirals into negative thinking, and make sure to put events in perspective [7]. Instead of imagining the worst case scenarios, or exaggerating negative events as the end of the world, it is important we become mindful of the way our brain reacts and purposefully rewire it through these small practices of positive thinking. To me, this is the key to keeping control of our minds during times of stress. Works Cited: [1] Conversano C, Rotondo A, Lensi E, Della Vista O, Arpone F, Reda MA. Optimism and its impact on mental and physical well-being. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2010; 6, 25–9. [2] Hecht D. The neural basis of optimism and pessimism. Exp Neurobiol. 2013; 22,173–99. [3] Riechers M. The science of looking on the bright side [Internet]. Wpr.org. 2019 [cited 2020 Nov 12]. Available from: https://www.wpr.org/science-looking-bright-side. [4] Harvard Health Publishing. Optimism and your health [Internet]. Harvard.edu. [cited 2020 Nov 12]. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/optimism-and-your-health. [5] Lee LO, James P, Zevon ES, Kim ES, Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Spiro A 3rd, et al. Optimism is associated with exceptional longevity in 2 epidemiologic cohorts of men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116, 357–62. [6] Achor S. The happy secret to better work. Ted. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/shawn_achor_the_happy_secret_to_better_work?language=en. [7] Shain S. How to be more optimistic. The New York Times [Internet]. 2020 Feb 18 [cited 2020 Nov 12]; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/18/smarter-living/how-to-be-more-optimistic.html.

1 Comment

Amit Bahl

1/20/2021 01:39:35 am

Well written, this again underscores the importance of establishing internal locus of control so as to give credit to oneself and accepting negative outcomes. Meditating and visualizing self in a positive environement (sometimes referred to as Reiki) leads to one following a postive path.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |