|

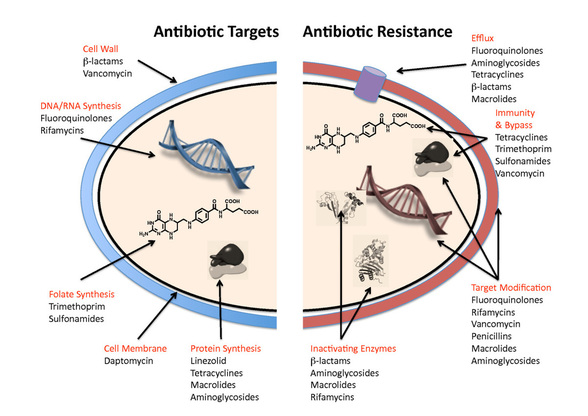

By Mitchell Yeary, '19 Almost everyone learns about the Black Plague in school, during what might have been one of the more exciting European or World history classes. It caused unpleasant symptoms like buboes (a funny word for the swelling of lymph nodes), killed anywhere from 30%-60% of Europe’s population, and gave us the nursery rhyme “Ring Around the Rosy”. Luckily, we don’t have to worry about the Plague, or lots of other infectious diseases anymore, as antibiotics make treating the bacteria responsible for them quite easy. Antibiotics were first discovered in the late 1920s by Alexander Fleming, when he noticed that a certain fungus Penicillium had antibacterial properties. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s there was a flurry of antibiotic research done, during which various classes of antibiotics were utilized to cure an increasing number of infectious diseases. In today’s world, unless we are talking about the latest outbreak like Zika or Ebola, we don’t think to much about infectious diseases. Yet it’s not just the new outbreaks of viruses that we need to be concerned about. There is a distinct possibility that infections we have been easily curing for decades might present a new threat, as they bacteria continue to become more resistant to available antibiotics.  Every year, over two million people are infected with bacteria that are resistant to all bacteria, and 23,000 people die from those infections. There has been increasingly growth in bacteria developing multi-drug resistances, and the pace at which we are developing new antibiotics to treat these infections is nowhere near where it needs to be. The problem is that we are not creating new classes of antibiotics, which has to do with what way each drug disrupts the function of bacteria, whether it is through binding to bacterial DNA or disrupting mitochondrial activity.In the 1940s and 1950s sixteen different classes of antibiotics were registered, and an additional twelve were introduced in the following three decades. Since the 1980s, however, there have been no new classes of antibiotic discovered. On top of that, the rate at which antibiotics are being developed by pharmaceutical companies and approved by the FDA has been decreasing steadily over the past few decades. Right now there are only 40 antibiotics in development phase, which sounds like a lot until you consider the fact that, historically, the FDA approves somewhere around 3% of the antibiotics that go through testing, and all 40 antibiotics being developed are derivatives of existing classes. This means that bacteria that are completely resistant to all currently available antibiotics will most likely still be resistant to the single antibiotic likely to be approved. This all paints a pretty grim picture of our future, one in which where the simple infections like bacterial meningitis (a nasty but curable illness) could have high fatality rates in even developed countries. Of course we can hope that the global community recognizes the gravity of the issue before we get to any point close to that. There are currently a couple of ideas out there that could bolster our antibiotic development, ranging from prize money set up by the government to changing the incentive scheme so that pharmaceutical companies are more likely to invest in developing new classes of antibiotics. The path leading forward is a difficult one, because there is a good chance we have discovered all the easily available antibiotic classes presented to us in the natural world. What is left are places of extreme biodiversity somehow secluded from human exploration, like the depths of the sea or the heart of the rain forest. Like with so many things, we may have to wait for this to be an acute problem, something very obviously affecting our world, as opposed to an issue we can push off into the future. Lets just hope we are up for the task when that moment comes. Sources:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3196380/ http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2016/05/a-scientific-roadmap-for-antibiotic-discovery http://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2016/05/13/a-plan-for-new-antibiotics https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2095020/#B3 http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/24/opinion/how-to-develop-new-antibiotics.html?_r=0

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |