|

By: Ashley Nee, ‘22 Edited by: Jess Sevetson

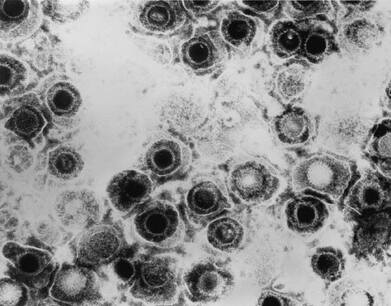

One such study was performed over the course of a decade in Taiwan. Researchers followed over 8,000 individuals over the age of 50 newly diagnosed with HSV-1 or HSV-2 infections. [1] There were over 25,000 control cases (matched to test cases based on age and gender) without HSV infections. [1] Strikingly, the risk of dementia development was 2.6 times greater in the group with HSV-1 or -2 infection as compared to the control group [1]. Even more persuasive, perhaps, is that a subset of the infected group who were treated with anti-herpes medications showed a near 10-fold reduction in Alzheimer’s development when compared to untreated individuals [1].

Evidence of HSV-1’s involvement in Alzheimer’s can also be seen in the lab. Several studies have implicated HSV-1 in affecting amyloid precursor protein processing [2]. Such findings are significant, as the breakdown of amyloid precursor protein is what generates amyloid-beta [2]. Further, other studies have demonstrated that HSV-1 infection can lead to neurodegeneration and phosphorylation of tau, a protein also implicated in Alzheimer’s disease [2]. While there are many other studies to support a connection between HSV-1 and Alzheimer’s, there remains a great deal of skepticism regarding this alleged connection. One molecular biologist from the University College London, John Hardy, argues that if amyloid-beta plaques were indeed a part of the brain’s immune response to HSV-1 infection, then aggregates would be more widely distributed in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, as this would be consistent with an infectious disease model [3]. Further, he contends that there is a widely accepted genetic component of Alzheimer’s disease, so even if HSV-1 is a part of the Alzheimer’s narrative, it is not the only factor driving the disease mechanism [3]. As articulated by Hardy, given the strong genetic component of Alzheimer’s, it is highly unlikely that HSV-1 is the sole cause of the disease. It may, instead, be one explanatory component for cases of Alzheimer’s that are sporadic rather than familial. Further, it is unlikely that a single incidence of infection would trigger a cascade of inflammatory responses that would result in prolonged neurodegeneration. Rather, recurrent infection of HSV-1 likely wears down the brain over time. As a person ages, his or her immune system weakens, so recurring HSV-1 infections and other factors may overwhelm the brain and lead to an inflammatory response in the form of amyloid-beta plaques. Such an idea is appealing by both the growth of evidence in support of it and because of the failure of many therapeutic drugs to effectively treat Alzheimer’s. Current drugs on the market work to prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter implicated in learning and in memory. However, these drugs are only effective in temporarily slowing the decline of cognition. This year, Biogen stopped clinical trials for its Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab, which worked to clear amyloid-beta plaques from the brain. Before Biogen ended trials for aducanumab, there was much hope for the drug, as it addressed what many scientists view as the central cause of Alzheimer’s: amyloid-beta. Yet, the drug’s failure in efficacy may hold a valuable lesson in future research endeavors and clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease: that Alzheimer's may be far more heterogenous in pathology than appreciated. In light of this, it seems high time for HSV-1 to gain momentum in research for future Alzheimer’s treatments and research. Citations: [1] Tzeng N.-S., Chung C.-H., Lin F.-H., Chiang C.-P., Yeh C.-B., Huang S.-Y., et al. Anti-herpetic medications and reduced risk of dementia in patients with herpes simplex virus infections-a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan [Internet]. 2018 [Cited March 27, 2019]. Neurotherapeutics. [2] Piacentini R, De Chiara G, Li Puma DD, Ripoli C, Marcocci ME, Garaci E, Palamara AT and Grassi C. HSV-1 and Alzheimer’s disease: more than a hypothesis [Internet]. 2014 [Cited March 27, 2019]. Frontiers in Pharmacology. DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00097 [3] Hardy J. Interviewed by The Scientist. September 1, 2017 [Cited March 29, 2019].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |