|

by Joseph Frankel '16

Purple brain + organic shapes = folk psychology? [image via]

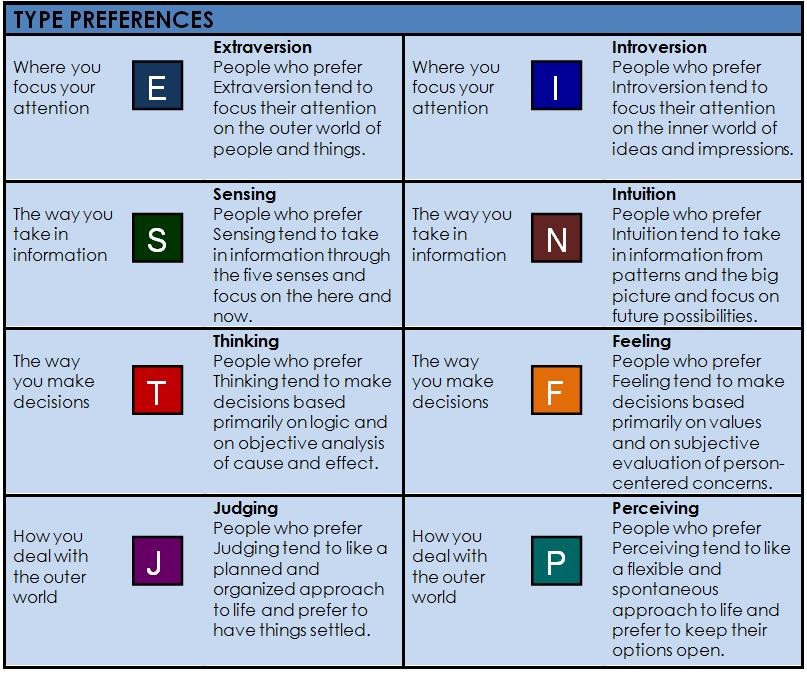

A month into the semester, a close friend revealed to me her firm belief in the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Sitting me down in front of her laptop, she directed me to an online version of the exam. About five minutes and 72 yes-or-no questions later, the test revealed that I am an ENFP, that I am more Extroverted than Introverted, more Intuitive than Sensory, more Feeling than Thinking, and more Perceiving than Judgmental. Immediately, I searched for information to help me interpret these findings. I found websites full of neat little graphics along with bit descriptions of each personality of the 16 personality types “in a nutshell.” Thus began my introduction to the cult of the MBTI. Used by over 10,000 companies, 2500 colleges, and 200 government agencies, the MBTI is the most widely used personality test in the world. Created during World War II by amateur psychologist Isabel Briggs Myers and her mother Katharine Briggs, the test’s initial purpose was to help women entering the workforce to replace men who’d gone to war determine in what line of work they’d be “most effective and comfortable” (1). Myers and her mother were avid followers of the work of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and based the test on his theory of types, that people would tend towards one or another style of interacting with the world along several different axes. In years since, it has ballooned into the go-to metric for human resource departments throughout the world in determining job placement, building teams, and career and academic advising.

"If one does not understand a person, one tends to regard him as a fool." [image via]

While I grew to identify with my personality type, as it explained aspects of my character that just couldn’t be coincidence, I began to wonder if I could really trust the MBTI, let alone take stock in its recommendations of what I should study, what I should do for a career, and what kinds of people I should aim to create relationships with. After all, all its recommendations were careers or majors I had at least briefly entertained. It was also a bit of a relief to finally have a reason to justify both my good and negative traits. So what if I don’t like conflict? It’s because I care about people too much. So I’m bad at organizing my workspace and getting to appointments on time? It’s not my fault – I’m Perceiving! But this excusing thought pattern led me to wonder whether the categories the test presented really made sense, let alone could give me a reliable sense of logic behind my actions and behaviors. After reading up on the MBTI, I was surprised and disappointed that I found a number of questionable aspects of the exam many critics cite as reasons to discontinue use of the MBTI in its current form. The most obvious of these flaws is the assessment of personalities based on a combination of arbitrary binary characteristics. While extroversion and introversion are opposing traits, the possible traits in the other three categories are not. It seems unlikely that a person could be exclusively intuitive or sensory, only feeling or only thinking, or perceiving and not judgmental. This aspect of the MBTI sets it apart from most other personality tests, which, following the principles of personality psychology, describe traits along continuous scales (2). From a statistical perspective, grouping personalities into two distinct traits along one scale only makes sense if those traits are bimodally distributed in our population. In other words, if the results of a survey determining whether people are ”feeling” or “sensory” were divided into two peaks, indicating that most people fall into only one category, this division would make sense. Almost no study on the MBTI has yielded data that fits this distribution of two main categories, so applying that methodology does not make sense in the case of the MBTI (3).

What's your type? [image via]

As far as the scope of the exam goes, the number and distinction between the types is also questionable. According to the MBTI, every single person fits into one of 16 categories. The thought that everyone on earth fits into one of those boxes is both extremely sobering and highly questionable. Critics of the MBTI emphasize the lack of real, qualitative differences between the categories themselves: the difference between an ENFP and an INFP would be nothing more than one letter. The two personality types are not actually distinct from each other in any way but that one trait, begging the question of how they can be considered distinct types rather than variations on the same type.

Critics also question the exam‘s basis on Jung’s work. Carl Jung, while a prolific and important psychologist, developed most of his theories through methods that would not be accepted as valid in modern psychology. But these flaws don’t change the fact that certification for and distribution of the MBTI is a multimillion dollar per year industry. Consultants, human resource workers, and individuals the world over still maintain an almost religious belief in the test. While any test result (especially an online test result) should be taken with a grain of salt, the idea of establishing recommendations for serious decisions in a person’s life on a flawed methodology is really worrying. At first, I was disappointed that the MBTI couldn’t really help me figure out what to major in, who to be around, and what to do with my life. But in the absence of this convenient blueprint, it is heartening that people just aren’t that simple, and that the work of figuring ourselves out can’t be reduced to four letters.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |