|

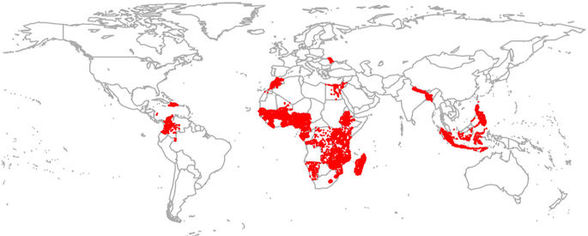

by Claire Bekker '21 How can ecosystems affect human health? How could forests prevent childhood disease? Researchers are investigating these connections in the context of climate change and environmental degradation. Especially in developing countries, there is a clear connection between ecosystem loss and infectious disease. Up to 24% of the global burden of disease (GBD) can be attributed to poor environmental quality [1]. Diseases that disproportionately affect children, such as malaria, respiratory infections, and diarrheal diseases, are often linked to poor environmental health. In fact, diarrheal disease, which is caused by contaminated surface water, is the second leading cause of death for children under the age of five [2]. This led researchers to investigate the link between diarrheal disease and the environment.  This map indicates where the data was derived from for this study. All of the data came from USAID (the United States Agency for International Development). This map indicates where the data was derived from for this study. All of the data came from USAID (the United States Agency for International Development). A new study conducted by researchers at the University of Vermont has found that the tree cover of a water source impacts the prevalence of childhood diarrheal disease (DD) downstream. They studied 300,000 children in 35 nations across Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and the Caribbean using USAID (the United States Agency for International Development) data from the last thirty years [3]. While controlling for other factors such as socioeconomics, climate, and sanitation, upstream tree cover still resulted in statistically significant less DD [3]. In rural areas, where people are more likely to drink surface water, the results were even more notable. A 30% increase in upstream tree cover resulted in a similar decline in disease as the use of indoor plumbing [3]. Researchers suggest two possibilities for these effects. First, forests supplant human activities, which contribute to water pollution and second, forests can remove or filter pollutants and pathogens before they enter the water source. While the effects are significant, Diego Herrera, who led the study at the University of Vermont, stresses that tree cover is not “more important than toilets and indoor plumbing" and instead complements sanitation infrastructure [4]. Overall, man-made infrastructure and environmental covering can be used together to prevent the spread of DD. It is unclear how the results of this study will be utilized in the future. Will the public health benefits of trees reduce deforestation? Will governments, communities, or nonprofit groups plant trees upstream to reduce infectious disease rates? The issue may depend on an economic cost-benefit analysis. Though trees could reduce medical expenses and contribute to a healthier population, they occupy land that can be used for other economic activities such as agriculture. Ultimately, developing countries must weigh the benefits of economic development and the cost to human health. The authors of this study caution readers that public health is an interrelated issue tied to wealth, education, infrastructure, human activity, and the environment. It is difficult to look at one issue in isolation. However, given the significant results of this study, more work can be done to investigate the relationship between the environment and disease. This study also reminds us that humans are deeply involved in and affected by our natural environment. The individual and collective actions we take impact all life on Earth and generations to come. By preserving ecosystems and wildlife, our own lives can be improved as well. Ultimately, our fate as a species depends on how we treat our planet. Sources

[1] Bauch, S. C., Birkenbach, A. M., Pattanayak, S. K., & Sills, E. O. (2014). Public Health Impacts of Ecosystem Change in the Brazilian Amazon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States, 112(24), 7414-7419. Retrieved October 14, 2017. [2] WHO. Inheriting a sustainable world: atlas on children’s health and the environment. http://www.who.int/ceh/publications/inheriting-a-sustainable-world/en/ (2017). [3] Diego Herrera, Alicia Ellis, Brendan Fisher, Christopher D. Golden, Kiersten Johnson, Mark Mulligan, Alexander Pfaff, Timothy Treuer, Taylor H. Ricketts. Upstream watershed condition predicts rural children’s health across 35 developing countries. Nature Communications, 2017; 8 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-00775-2 [4] University of Vermont. "Global kids study: More trees, less disease." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 9 October 2017. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/10/171009084403.htm>.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |