|

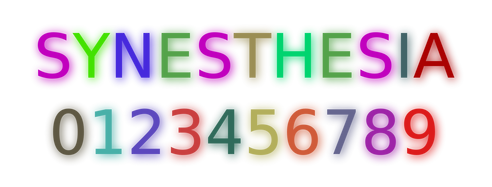

by Jennifer Maccani, PhD  The painter Wassily Kandinsky was a well-known synesthete who saw music. [image via] If you’re a fan of classical music, you’ve likely spent a rhapsodic hour daydreaming to the lilting melodies of Beethoven’s sixth symphony, the “Pastoral,” so-named because the music is said to evoke images in the mind’s eye of rolling fields, fluttering streams, and tinkling birdsong. Yet, for roughly 0.05-1% of the population (1), Beethoven’s masterpieces can evoke far different—and far more vivid—imagery. For these people, music and/or other sensory stimuli trigger immediate perceptions that feel as real as the music itself, often in the form of color and shape (2, 3). These people were born with what some might consider a real-life superpower, a condition called synesthesia. The most common type is grapheme-color synesthesia, in which letters or numbers elicit colors in the mind’s eye. For synesthetes, these colors are an essential part of the letters or numbers themselves, almost a part of their essence or identity (4). However, over 60 types of synesthesia have been identified in the population; in fact, there may be 150 or more distinct types (5). Music can evoke spatial sensations, shapes or colors (6-8); words can taste sour or sweet (9); voices can look like grey smoke or dry, cracked soil (9, 10); or the sound of a car horn can smell like strawberries (11). Even the personalities of one’s family and friends can have their own distinct colors (12). Individuals may have only one type, or several, and some of them—such as voice-color and personality-color synesthesia—are rarer than others.  To learn more about this xkcd comic, head over to explainxkcd. [image via] Synesthesia is more than color association. For synesthetes (people with synesthesia), responses are both automatic and consistent (6), and the same responses occur nearly every time a particular stimulus is encountered—often for most of a person’s life (13). Whether synesthesia is a one-way street, with numbers evoking colors but not the other way around, is still up for debate; in some individuals, evidence suggests that colors may unconsciously serve as keys for the stimuli that produce them, serving as a kind of color code (13). In one study, synesthetes who see color in response to numbers were able to complete math problems just as quickly with patches of color as they could with the numbers themselves (14). This is only one benefit of synesthesia, and it illustrates one potential reason that synesthesia may have evolved in the first place. Some research has suggested that synesthesia may aid in the learning of language or categories (15, 16). In addition, improved color sensitivity, color working memory, mental rotation ability, and mental imagery have all been described in synesthetes, although motion perception may be impaired in some individuals (2, 17-23). Synesthesia requires attention to produce an effect, though, and the majority of individuals see color or shape in their mind’s eye only (24). Interestingly, although synesthetic perceptions vary widely from one individual to the next, some similarities have been described for certain types of synesthesia. For example, many people with grapheme-color synesthesia perceive the letter “A” to be red, and the day Sunday to be white (25). These pairings—or “perceptual representation systems,” as scientists call them (25)—are typically formed very early in childhood, although time of development can vary (26). For almost half of synesthetes, these systems are fixed by the age of 7 or 8; for more than 70%, by age 10 or 11 (26).  Some synesthetes see letters and numbers as having their own colors. [image via] Though scientists have tried since 1934 to train non-synesthetes to produce synesthetic responses, they have been unable to do so, making it likely that synesthesia is caused by inherent genetic or structural differences in affected individuals, rather than environmental factors . Aside from certain currently unanswerable questions about synesthesia—for example, how do synesthetes tell their perceptions from physical reality? (41)—one common question non-synesthetes often ask is: what is it like to be synesthetic? With emerging technology, you may be able to find out. Several apps have recently been developed that approximate synesthetic experiences. One such app is “Roy G Biv” by Julian Glander, which allows users to translate colors into music via their phone. Color data is converted into 8-note synth modulations, so you can find out what chartreuse sounds like, or if chocolate cake sounds as delicious as it tastes. Another similar app is Stromatolite’s “Synaesthesia”, which allows users to scan colors and convert them into music. Tilting one’s phone changes the pitch; shaking creates beats. Of course, if “Roy G Biv” and “Synaesthesia” are too whimsical for your taste, you can try the “ChoiceMap” app by Jonathan Jackson, which approximates its creator’s synesthesia to help users think through decisions (42). Jackson’s synesthesia helps him to visualize his decision-making processes by transforming what he intuitively feels about his choices into a geometric map or model of his priorities. Like other synesthetes, his sensory perceptions are instinctive and immediate, so he never put pen to paper to describe it until he set about making “ChoiceMap.” He discovered that he could create a mathematical algorithm to approximate the models he saw in his mind into an interface users could better understand, allowing others to take advantage of a decision-making process that, to Jackson, is second nature. ChoiceMap intro video from ChoiceMap on Vimeo. While these apps are a great start at approximating and allowing others to benefit from synesthesia, they’re a far cry from allowing non-synesthetes to see the world as synesthetes do: full of colors, textures, and shapes overlaid atop the physical world on a plane that can’t be accessed by or described fully to others. When will non-synesthetes be able to experience synesthetic colors that don’t exist in the physical world, or see the undulating hues evoked by Beethoven’s “Pastoral” symphony? Only time will tell. As research progresses, perhaps we’ll gain a better understanding of the boundaries of our senses, of what it means to perceive, of what “real” really means. References

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |