|

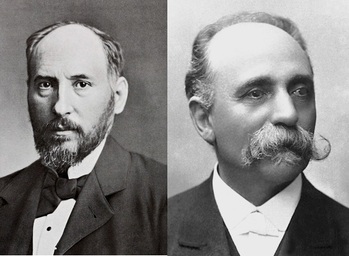

A Review of Advice For A Young Investigator by Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Translated by Neely Swanson & Larry W. Swanson) by Matthew Lee '15  [image via] [image via] Find this book in the Sci Li! Or read the full text online! Paperback: 176 pages Publisher: Bradford Books, The MIT Press (1999) ISBN-13: 978-0262681506 In 1906, two rival neuroscientists shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine: Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Golgi firmly believed in the reticular theory, that the brain consisted of a single network. In contrast, Cajal contended that the brain actually consisted of discrete cells. As it turns out, Cajal was right. Cajal (1852-1934), who hailed from Spain, spent years at a microscope and painstakingly drew neurons. After all, it would be quite some time before we would be able to take pictures of cells. His descriptions and depictions of the nervous system are so detailed that they serve as a foundation for modern neuroanatomy.  A section of a sparrow's optic tectum. [image via] Well into his career but a decade before winning the Nobel Prize, Cajal wrote Advice for a Young Investigator, a short guide rife with humor, anecdotes, and timeless wisdom for students aspiring to become great scientists. The book was so popular three more editions were published over the next twenty years. In 1999, Neely Swanson and Dr. Larry W. Swanson released a translation that preserves Cajal’s straightforward, yet eloquent, prose. It’s fine if your favorite scientist is Einstein, but if you’re an aspiring physicist, Cajal cautions against idolatry: I believe that excessive admiration for the work of great minds is one of the most unfortunate preoccupations of intellectual youth—along with a conviction that certain problems cannot be attacked, let alone solved, because of one’s relatively limited abilities…. There is certainly no reason to envy our predecessor, or to exclaim with Alexander following the victories of Philip, “My father is going to leave me nothing to conquer!” In doling out advice, Cajal addresses several issues that are just as relevant today. Trying to decide between an ScB in Chemistry and Chemical Engineering? Cajal harpoons the “false distinction between theoretical and applied science, with accompanying praise of the latter and depreciation of the former.” Instead, he suggests: Let us cultivate science for its own sake, without considering its applications. They will always come, whether in years or perhaps even centuries. Besides, ChemEngn requires more courses.  Drawings of adult motor cortex, adult visual cortex, and infant cortex (left to right). [image via] Cajal also stresses that budding young scientists should study things other than science: More than anything, the study of philosophy offers good preparation and excellent mental gymnastics for the laboratory worker. tackles what he considers the biggest distinction between the sciences and humanities: Because art depends on popular judgments about the universe, and is nourished by the limited expanse of sentiment, it has had time to drain virtually all of the emotional content from the human soul… In contrast, science was barely touched upon by the ancients, and is as free from the inconsistences of fashion as it is from the fickle standards of taste. and calls out stubborn politicians in a footnote: In politics, the worship of inflexibility or resistance to change is considered a virtue, whereas in science it is almost always an unmistakable sign of pride or shortsightedness…. [H]e who cannot abandon a false concept brands himself as either stupid, dated, or ignorant. Only fools and those who don’t read persist in error.  "There is no such thing as global warming." [image via] Later on, Cajal teases teachers who never contribute original work (contemplators, bibliophiles, megalomaniacs, theorists), offers some dated advice on whom scientists should marry (“intellectual young women… overflowing with optimism and courage”), criticizes Spain for not giving enough money and resources to research institutions, quotes Gracián on how to write scientific articles well (“One should speak as in a will—fewer words means less litigation”), and discusses how an established scientist should identify and nurture students. The book is short, sweet, and hits a lot of great points. I’ve always loved to read old books because they provide a glimpse into a time and culture that has long since faded but whose effects can still be felt in the present. The culture of scientific research doesn’t seem to have changed much over the last century. Moreover, as an aspiring scientist myself, I found it comforting that Cajal could point out mistakes I was making and give me insight into what being a scientist really means. Of course, as with all advice, take Cajal’s with a grain of salt. We may learn a great deal from books, but we learn much more from the contemplation of nature—the reason and occasion for all books.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |