|

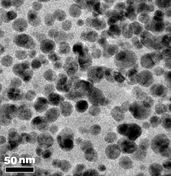

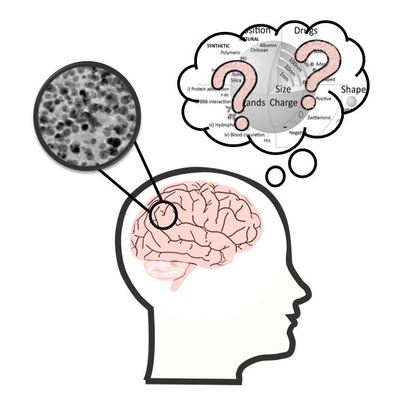

by Michelle Muzzio, 2nd Year Chemistry PhD Student  Don’t worry, it is all in your head. Typically considered a trivial idiom, this phrase becomes a bit more alarming when “it” is magnetic nanoparticles and “it” is backed by experimental and theoretical data. A recent study published in PNAS by Maher et al. highlights the presence of exogenous (not of a biological origin) iron, cobalt, nickel, and even platinum nanoparticles in human brain samples. The work has been picked up by popular science outlets and major media alike such as Science Magazine, Newsweek, Chemical and Engineering News, and the Huffington Post. Crossing the publication-to-publicity barrier is a feat that most publications will never accomplish with their primary demographic being frazzled graduate students, uninspired postdocs, and curious-but-skeptical professors. What then is the responsibility (if any) of the scientific papers that journey into the promised land of trending and retweeting? When science leaves the laboratory and then also leaves the carefully veiled community of publications and conference proceedings, the successful communication of science (or lack thereof) becomes a science in and of itself.

1 Comment

Olivia

11/27/2016 11:27:55 am

I like the brain animation!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |