|

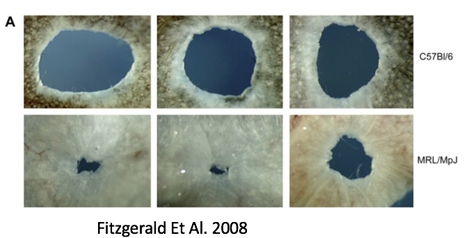

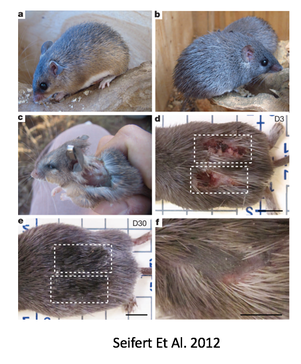

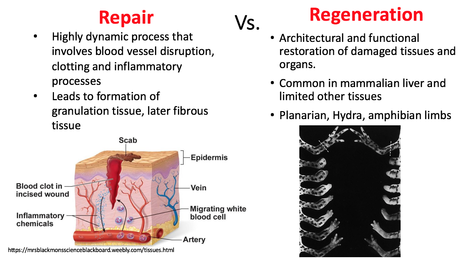

by Olivia Woodford-Berry, '19 While some organisms, including certain salamanders and planarian, have the capability to regenerate tissues, limbs, or even large segments of the body, mammal regeneration is much more restricted. [1] Mammals often possess the ability to regenerate tissues in their embryonic stages, but the adult organisms usually heal through the formation of fibrotic scar tissue. The varied regenerative limitations within this class of organisms is of particular interest for the field of tissue engineering and wound healing. Many researchers aspire to uncover the biological processes that allow certain organisms to heal so effectively with the hopes of adapting these processes for humans. While most regenerative studies surround non-mammalian model organisms, certain mice lines show great promise for future regeneration research in mammals.  In mammals, wound repair is achieved primarily through tissue repair as opposed to regeneration. Repair is characterized by complex processes that involve the disruption of blood vessels, clotting, the initiation of immune responses, and the formation of granular tissue. [2] This will eventually lead to fibrotic scarring, and in the case of cartilage damage, weaker tissues overall. Studies have shown that restored cartilage in humans does not have the same resistance to biomechanical force as the original tissue. This means that one injury can often lead to further cartilage damage, cartilage erosion, and later, osteoarthritis. [3] In contrast, regeneration, defined as architectural and functional restoration of damaged tissues, bypasses any consequences of normal repair responses. For this reason, research seeks to identify concrete differences between the genetic controls of these processes and examine how regeneration could be activated in mammalian adults. New research has shown that certain mouse species have regenerative capacities thought to not exist in mammals. Recent studies suggest that MRL/MpJ mice, an inbred strain of laboratory mice originally used to study Lupus, have an intrinsic ability to bypass the normal fibrotic ‘repair’ response and instead implement a more ‘regenerative’ processes of tissue restoration through the formation of a blastema-like structure—which involves the aggregation of undifferentiated cells. One study found that these mice demonstrated full ear-wound closure at a rate much faster than that of the control mice. Likewise, adult MRL/MpJ mice have the capacity to regenerate new hair follicles and sebaceous glands in new growth areas. [4] Further studies have continued to explore the regenerative abilities of these mice, and research has shown that these mice also demonstrate exceptional regeneration in retinal pigment cells and in cardiac tissue. [5][6]  Currently, subsequent research aims to explore the genetic mechanisms which propel mouse regeneration, and studies have shown that this strain maintains certain features of embryonic metabolism through adulthood. These factors include but are not limited to the enhanced expression of the key stem cell markers Sox2 and Nanog. [7] In addition, these mice have a deficiency in the inhibitor p21, resulting in an increased number of cells that skip the G1 checkpoint and stay in in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. [8] Although the exact reasons are unknown, this deficiency has been correlated with enhanced healing abilities. Overall, 36 genes have been identified as good candidates for factors that may explain the exceptional healing abilities in these organisms. [9]

Sources:

1. Shastri, Devi. "How some salamanders regrow their limbs." Science, June 29, 2016. 2. Werner, Sabine, and Richard Grose. "Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines." Physiological reviews 83, no. 3 (2003): 835-870. 3. Hunziker, E. B. "Articular cartilage: composition, structure, response to injury and methods of facilitation repair.” Ewing JW: Articular cartilage and knee joint function basic science and arthroscopy Bristol-Meyers/Zimmers Orthopaedic symposium." (1990): 19-56. 4. Fitzgerald, Jamie, Cathleen Rich, Dan Burkhardt, Justin Allen, Andrea S. Herzka, and Christopher B. Little. "Evidence for articular cartilage regeneration in MRL/MpJ mice." Osteoarthritis and cartilage 16, no. 11 (2008): 1319-1326. 5. Xia, Huiming, et al. "Enhanced retinal pigment epithelium regeneration after injury in MRL/MpJ mice." Experimental eye research 93.6 (2011): 862-872. 6. Leferovich, John M., Khamilia Bedelbaeva, Stefan Samulewicz, Xiang-Ming Zhang, Donna Zwas, Edward B. Lankford, and Ellen Heber-Katz. "Heart regeneration in adult MRL mice." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, no. 17 (2001): 9830-9835. 7. Górnikiewicz, Bartosz, Anna Ronowicz, Justyna Podolak, Piotr Madanecki, Anna Stanisławska-Sachadyn, and PaweŁ Sachadyn. "Epigenetic basis of regeneration: analysis of genomic DNA methylation profiles in the MRL/MpJ mouse." DNA research 20, no. 6 (2013): 605-621 8. Fitzgerald, Jamie. "Enhanced cartilage repair in ‘healer’mice—New leads in the search for better clinical options for cartilage repair." In Seminars in cell & developmental biology, vol. 62, pp. 78-85. Academic Press, 2017. 9. Masinde, Godfred, Xinmin Li, David J. Baylink, Bay Nguyen, and Subburaman Mohan. "Isolation of wound healing/regeneration genes using restrictive fragment differential display-PCR in MRL/MPJ and C57BL/6 mice." Biochemical and biophysical research communications 330, no. 1 (2005): 117-122. 10. Seifert, Ashley W., Stephen G. Kiama, Megan G. Seifert, Jacob R. Goheen, Todd M. Palmer, and Malcolm Maden. "Skin shedding and tissue regeneration in African spiny mice (Acomys)." Nature 489, no. 7417 (2012): 561-565.

2 Comments

12/3/2019 03:52:57 am

Dear Colleagues,

Reply

3/13/2020 07:48:06 am

Greetings from Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2020!!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |