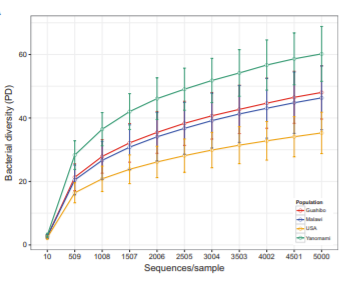

Maintaining Your Microbes: Promoting Gut Microbiome Diversity and Health in the Modern Era8/22/2021 Written by: Jon Zhang '24 Edited by: Owen Wogmon '23 Microorganisms, or microbes, include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other organisms. The collection of microorganisms composing an environment is called a microbiome. In the human gut microbiome, trillions of microbes exist inside a pouch called the cecum, right at the connection between the small and large intestines [1]. These microbes play a vital role in our lives from the moment we are born. Babies inherit microbes from their parents, most notably bacteria called Bifidobacteria that promote digestion of breast milk. As babies grow, their gut microbiomes diversify, and this greater variety is linked to better health. Examples of positive impacts include reduced weight, improved regulation of blood sugar to lower the risk of diabetes, and increased resistance against intestinal diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease [1]. However, scientists warn that the diversity of gut microbes is on the decline, describing this trend as a consequence of modernization. In a collaborative study between American and Venezuelan researchers published in 2015, the team studied residents of a remote Yanomami village, an indigenous tribe living along the border between Brazil and Venezuela. This tribe has remained isolated for over 11,000 years, meaning that the subjects had virtually no exposure to 21st-century society. Without modern food production and biomedicine, the Yanomami forage for wild fruits, hunt small animals, and treat themselves with herbal medicine. In this manner, the tribe has maintained a lifestyle similar to that of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, offering researchers the unique opportunity to assess the influence of modern life in depleting the human gut microbiome [2]. The scientists analyzed 12 stool samples from Hadza participants to use as a proxy for analyzing their gut microbiomes. While less conclusive than a biopsy, which would involve directly removing tissue from the gastrointestinal tract, this method is more convenient and less invasive, which are important considerations when conducting an experiment on subjects with no previous exposure to modern medicine. The microbiologists extracted the DNA from samples and sequenced the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene, a region known to characterize the gut. Then, they calculated Faith’s phylogenetic diversity, a metric of biodiversity, and compared it to American subjects [2]. The researchers noticed an unprecedented level of microbiome diversity in the Yanomami subjects, with nearly 50 percent greater bacterial diversity than Americans. They also compared the Yanomami data with two earlier studies examining microbial diversity across different geographic regions and went so far as to declare, “The microbiome of the uncontacted Amerindians exhibited the highest diversity ever reported in any human group.” While this conclusion is based on a small sample size, this investigation was one of the first to illuminate the extent to which Westernization has altered the human gut microbiome [2]. A team of microbiologists from Stanford University led a similar study but with a focus on diet. These researchers collected 350 fecal samples from the Tanzanian Hadza tribe from 2013 to 2014 to assess the levels of diversity in their guts. The team then compared their findings with data from the Human Microbiome Project and confirmed that the variety of gut microbes tends to be greater in diets that deviate from a standard Western diet -- one that is high in processed foods, unhealthy fats, and refined sugars [3].

However, the researchers made another discovery that provides a more nuanced understanding of how diet may impact gut microbial diversity. They examined operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for two different phyla, or taxonomic categorizations, of gut bacteria: Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. The researchers noticed that some bacteria species became temporarily undetectable during seasonal transitions between the dry season (May to October) and the wet season (November to April). 70.2% of Bacteroidetes OTUs disappeared between the 2013 late-dry and 2014 early-wet seasons, with 78.2% of these reappearing at later points in time. Conversely, 62% of Firmicutes OTUs disappeared with the onset of the 2014 early-dry season, with 76% reappearing throughout the following wet season. The researchers connected these fluctuations in the presence of bacteria with Hadza dietary patterns. The Hadza participants eat more meat during dry seasons when conditions are favorable for hunting. During the wet seasons, however, the Hadza consume more wild berries and honey. This remarkable finding suggests that the composition of the human microbiome is dynamic, reconfiguring itself in response to dietary transitions. This study offers hope that the overall Western trend of decreasing microbial diversity might be reversible if we alter our diets [3]. So, what changes should we make? While the researchers conducting the Hadza experiment were unable to uncover why certain foods restore gut microbial levels, scientists involved in the PREDICT 1 project analyzed and sequenced the gut microbes of 1,098 participants to uncover how diet can promote the helpful microbes we already have. The scientists identified 30 bacteria species as markers of overall health. For example, a species known as Firmicutes bacterium CAG:95 was closely linked to beneficial health effects such as decreased heart disease and diabetes risk, while a genus known as Clostridia indicated poor health. The researchers analyzed the diets of these participants and, perhaps unsurprisingly, they found correlations between better health and more nutritious foods. Particularly, high-fiber plant foods including spinach, broccoli, and nuts as well as minimally processed animal foods like fish, eggs, and full-fat yogurt promoted beneficial gut bacteria. Lower-fiber alternatives such as fruit juices and highly processed meats like bacon were detrimental to microbiome health. Although these are general findings and dietary needs will vary from person to person, the right foods can promote microbiome health [4]. Just one more reason to switch to a Mediterranean or vegetarian diet. Gut microbiome diversity and robustness play a crucial role in determining overall human health. Scientists have noticed a decline in diversity associated with industrialization and modernization. Fortunately, groundbreaking discoveries into cycles of disappearance and reemergence of gut bacteria present promising signs that we can alter our diets to restore gut microbiome diversity. In the meantime, though, the food we eat plays an influential role in shaping our gut health; consuming naturally sourced foods high in fiber seems to be one of the most immediate changes we can make. All in all, insights into the human gut microbiome provide greater insight and understanding into human physiology and can help individuals make better-informed, more healthful choices. Sources: [1] Robertson R. Why the Gut Microbiome Is Crucial for Your Health [Internet] [Cited 2021 July 11]. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/gut-microbiome-and-health [2] Clemente JC, Pehrsson EC, Blaser MJ, Sandhu K, Gao Z, Wang B, et al. The microbiome of uncontacted Amerindians. Science Advances [Internet]. 2015 [Cited 2021 July 11]; 1(3), 1-12. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500183 [3] Smits SA, Leach J, Sonnenburg ED, Gonzalez CG, Lichtman JS, Reid G, et al. Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science [Internet]. 2017 [Cited 2021 July 11]; 357(6353), 802-806. DOI: 10.1126/science.aan4834 [4] Asnicar F, Berry SE, Valdes AM, Nguyen LH, Piccinno G, Drew DA, et al. Microbiome connections with host metabolism and habitual diet from 1,098 deeply phenotyped individuals. Nature Medicine [Internet]. 2021 [Cited 2021 July 11]; 27, 321-332. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01183-8 [Image] Harris R. Human microbiome, conceptual illustration [Internet] [Cited 2021 July 11]. Available from: https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/921652/view

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |