|

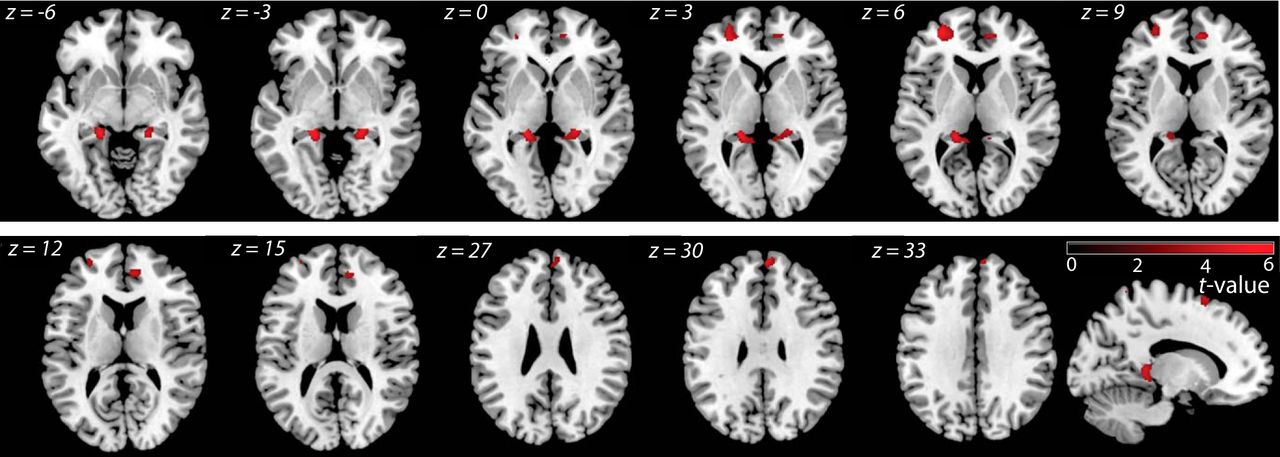

By: Maya Mazumder Edited by: Priya Gajjar Lucid dreaming is an aspect of sleeping that continues to puzzle neuroscientists. Lucid dreaming, or gaining consciousness of the fact that one is dreaming, is an area of research with exciting potential applications. While lucid dreaming has been recognized in the public consciousness since antiquity, researchers have only recently begun to understand the complex processes that trigger and differentiate lucid dreams from normal dreams. In the past several decades, new technology, such as the electrooculogram (EOG) and fMRI, has allowed neuroscientists to identify a biological basis for lucid dreams and explore their characteristics further. A recent compilation of studies on the neuroscience of lucid dreaming, published in the Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience, provides an excellent overview of contemporary understanding and future directions for research into the phenomena. [1] In particular, lucid dreaming offers a unique opportunity to understand higher orders of consciousness (consciousness beyond the present that allows for unique self reflection, regulation, and planning). This is an aspect of processing that is normally lost during dreams, but appears to be retained during lucid dreams. For most people, dreams consist of the “remembered present,” or a consciousness that only extends to the moment they are in, whereas during lucid dreams people appear to be able to think beyond the present moment and engage in metacognition. Due to this apparent shift in thought, researchers are able to document significant differences in brain activity during normal and lucid dreaming in order to find cortical areas associated with higher consciousness. In particular, by using a combination of EEG, PET, and fMRIs to track brain activity during sleep and wake, studies indicate that areas in a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex are more active during lucid dreams than normal REM sleep, and additionally that people who report more frequent lucid dreams possess more grey matter, or neuronal cells, in these same areas. [1] Both of these pieces of evidence support the idea that cognitive processes associated with the prefrontal cortex are at work during lucid dreaming. Interestingly, these areas of the cortex have been implicated in processes like appraising one’s thoughts or feelings, and other functions that are generally lost in dreams. Further exploration of brain activity in these cortical areas has the potential for greater understanding of the complicated functions of these areas. Additionally, physiological data on lucid dreaming could potentially be used to investigate pharmacological approaches to trigger lucid dreams, possibly for treatment of various psychological disorders, especially PTSD and chronic nightmares. [1] Several recent studies have found that by administering a drug that increases access to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, people have an increased likelihood of experiencing a lucid dream. For someone suffering from PTSD who consistently experiences intense flashbacks during dreams, being able to gain conscious control and change the narrative of a dream has the potential to reduce emotional distress. Similarly, with further research into activating the metacognitive processes associated with lucid dreaming, some neuroscientists see the potential to understand and treat psychosis, as those same functions are often lost during a psychotic experience. The applications for research into lucid dreaming is incredibly broad, and many ideas have yet to even be explored in depth. Citations: [1] Benjamin Baird, Daniel Erlacher, Michael Czisch, Victor I. Spoormaker, Martin Dresler, Chapter 19 - Consciousness and Meta-Consciousness During Sleep, Editor(s): Hans C. Dringenberg, Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience, Elsevier, Volume 30, 2019, Pages 283-295, ISSN 1569-7339, ISBN 9780128137437, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813743-7.00019-0. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128137437000190) Image from: Filevich et. al, 2015

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |