|

by Matthew Lee '15 “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.”

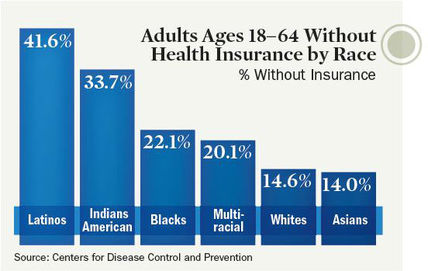

To prove that healthcare disparities do exist and are problematic, Dr. White presented several examples of how the healthcare system treats minority groups differently. For example, African-Americans receive fewer liver transplants and are more likely to undergo amputations due to complications from diabetes than other racial groups. Also, Hispanic-American adults are less likely to receive flu shots and other vaccines than non-Hispanic white adults.  Many minority communities lack access to health insurance. [image via] These disparities are associated with the healthcare system but they arise from individuals’ biases. Likening racism to an iceberg in that only 10% is visible, Dr. White argued that both denial (“Racism doesn’t exist”) and acceptance (“Everyone’s racist”) of racism obstruct awareness of racism’s deep roots. However, most of us stand somewhere in the middle of that spectrum, able to recognize blatant injustices but perhaps unaware of how we may also contribute to systematic discrimination. Accordingly, he encouraged everyone to uncover their own biases by taking the Implicit Association test, which attempts to identify our latent opinions on gender, religion, race, sexuality, disability, and weight. In certain cases, physicians’ IAT scores have revealed unconscious biases and predicted treatment decisions. Dr. White pointed out that our biases are malleable but that it is up to us to avoid media that reinforces negative stereotypes. In fact, he advised us to seek people and media that challenge our stereotypes. Dr. White highlighted suggestions made in a 2009 review on how to eliminate healthcare disparities by improving health literacy, educating caregivers, increasing the diversity of caregivers, and educating patients. He emphasized that patients should proactively learn about both their conditions and healthful living from reputable sources such as WebMD or the Mayo Clinic. He also lauded a New Jersey law that has required physicians to undergo training in culturally competent care since 2005. While national standards for culturally appropriate services reflect the right direction, healthcare professionals ought to hold themselves accountable for meeting them. In the exam room, Dr. White offered suggestions for both physicians and patients. Physicians should get to know their patients as fellow human beings, not simply walking conditions. For example, a relatively simple way to humanize a patient with diabetes is to eschew the term “diabetic” for “person with diabetes”—it’s worth the three extra syllables. Similarly, patients should humanize their doctors. Medical exams should end with “teach-back”: the patient recounts what they understand about their condition and how to treat it. This exchange allows the important messages to solidify in the patient’s memory and provides an opportunity for the physician to correct or add to the patient’s knowledge. Of course, if you don’t think your relationship with your doctor is working, Dr. White advised, communicate your concerns. If that doesn’t improve anything, find another doctor.  Doctors and patients must work together to achieve lasting positive outcomes. [image via] Throughout the lecture, Dr. White underscored the commonness and humanness of our common humanity. Moments of vulnerability, which are especially prevalent and pronounced in healthcare settings, form an important part of what makes us human and binds us together. Dr. White encouraged everyone in the audience to “be active in your sphere of influence,” to do what we can to make the world a nicer place to live. We’re all in this together—we might as well meet each other halfway.

To learn more about healthcare disparities in the United States, check out these findings from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |