|

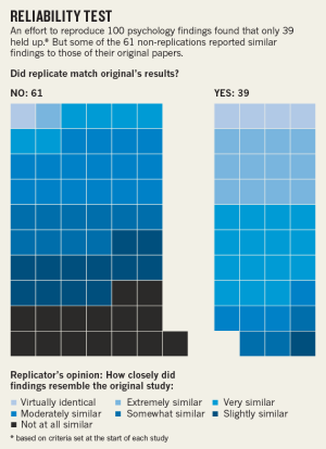

Elena Renken '19 With the abundance of research taking place at Brown, and countless journals offering glimpses into the often inaccessible realms of countless scientific fields, we are surrounded by information. Answers abound, but how much faith can we place in them? Take psychological research as an example.  A September article in Psychological Science detailed a study led by Steven Sloman, a CLPS professor at Brown. The paper suggested that "despite the absence of any actual explanatory information, people rated their own understanding of novel natural phenomena as higher when they were told that scientists understood the phenomena than when they were told that scientists did not yet understand them." Giving evidence for the "community-of-knowledge" hypothesis, these experiments reinforced how our impressions of others influence our confidence about research. If our beliefs are mediated by influences like our perceptions of scientists' understanding, our comprehension and acceptance of scientific information is not completely evidence-based. This is further exemplified in a 2007 study which revealed that people tend to rate the scientific reasoning of cognitive neuroscience research more highly when it is accompanied by images of the brain, as opposed to no image or a bar graph. The authors argue that these brain images appeal to "people's affinity for reductionistic explanations of cognitive phenomena," giving people a concrete visual to ground their understanding. (They did not include a brain image in their study, although apparently readers might have been more impressed if they did.) Surely there are countless ways that internal influences affect our perceptions of scientific research—our human natures and complex mental processes constantly shape our knowledge acquisition. But there are factors inherent to the research itself that also question the faith we place in scientific studies. Try as we might to edit all bias out of experiments and studies, it persists and crops up in every step of the process from design to publication. Bias that creates evidence of relationships where none might actually exist is especially concerning in its ability to spread false ideas. A 2015 project that replicated 100 psychological studies found that only "one-third to one-half of the original findings were also observed in the replication study." Although this replication project was critiqued for its lack of sensitivity to context, among other issues, the shadow of doubt it cast on the reliability of psychological research remains. And it begs the question of how much trust should be placed in a study that suggests studies aren't to be trusted. Though psychological research may attract more skepticism than other fields, especially considering the much-discussed results of this replication project, similar questions can be asked of research in other STEM fields. The reliability of researchers' conclusions and our perceptions of them is not a forgone conclusion. The value of objectivity in scientific research still kept on a pedestal, and scientists retain their societal role as beacons of knowledge. But are we too easily persuaded by their findings? sources: http://pss.sagepub.com/content/early/2016/09/26/0956797616662271.long http://www.imed.jussieu.fr/en/enseignement/Dossier%20articles/article4.pdf http://science.sciencemag.org/content/349/6251/aac4716 http://www.nature.com/news/over-half-of-psychology-studies-fail-reproducibility-test-1.18248 http://www.pnas.org/content/113/23/6454.abstract

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |