|

Written by: Jon Zhang ‘24 Edited by: Angelina Cho ‘24, Elizabeth Ding ‘24 Anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) like carbon dioxide are undeniably responsible for accelerating climate change, creating an unprecedented rise in global temperatures and the frequency of extreme weather events. In 2015, delegates from every nation convened to address the impending threat of global warming, approving the Paris Climate Agreement. This monumental achievement marked the most ambitious international collaboration yet against climate change. Virtually every country vowed to prevent a worldwide temperature increase of 2℃ above pre-industrial temperatures throughout the 21st century and strived to limit it to 1.5℃ [1]. While 1.5-2℃ may not seem a lofty goal, recent trends suggest that increasing human activity will make this difficult to achieve. Records from NASA, NOAA, and other organizations determined that global temperatures have risen by 1℃ since temperatures were first recorded in 1880. More alarmingly, the majority of warming has occurred since 1981 at an average rate of 0.18℃ per decade [2]. Assuming this rate stays perfectly constant without increasing (which is unlikely), temperature increases will easily surpass the 1.5℃ benchmark, and in all likelihood, 2℃ as energy demands grow.

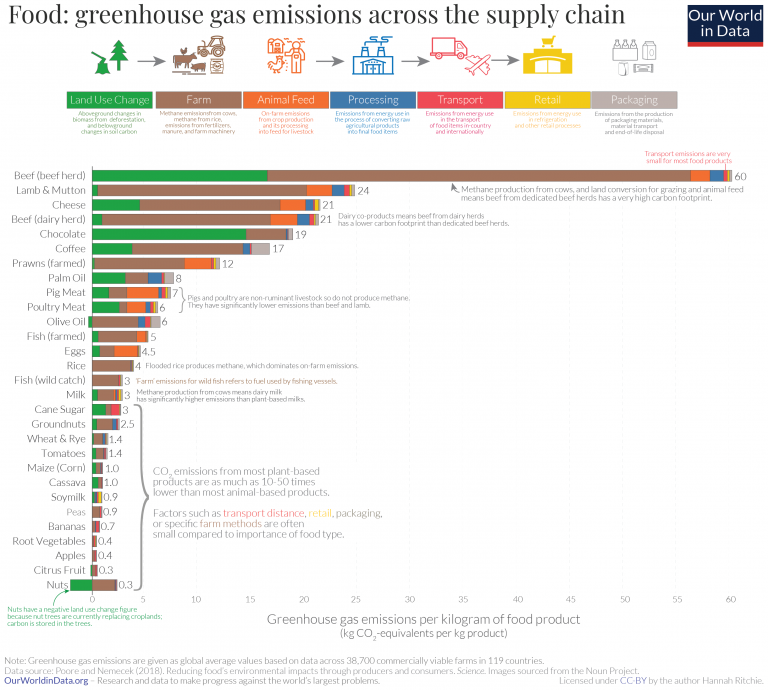

Clearly, all individuals must take drastic measures to minimize their carbon footprints. Most efforts have focused on fossil fuels, but the harsh reality that many seem reluctant to acknowledge is that confronting global warming must involve altering our lifestyles, not just our energy systems. Thus, I am writing to encourage all of us to make one change that will immediately lower our carbon footprints: STOP eating beef now. I know this seems like a tall order. I admit that I may indulge in a steak for special occasions or crave a hamburger every so often. But after learning about food-related contributions to climate change in an environmental science class, I chose to stop regularly consuming beef and severely limit my intake of other high-emission foods. I decided that it was a sacrifice I was willing to make for the planet and is a potential lifestyle change that everyone can make. In a culture where meat features prominently in every meal, this task may seem daunting, even amongst environmentalists. A few years ago, I attended a meeting of my high school’s Campus Democrats organization, where we initially sat together and ridiculed the illogicality and stubbornness of climate-change skeptics. And yet, moments later, the same individuals turned a blind eye towards their own actions. When someone brought up the impact of red meat on the environment, the people I had been nodding along with earlier scoffed at the prospect of restricting meat consumption. I watched fellow students and even the faculty sponsors dismiss the idea one-by-one. Dozens of my like-minded peers stood together against an effort that would help remedy the climate crisis we unanimously acknowledged minutes earlier. Despite the challenges in adapting our diets, I believe that the looming crisis of climate change must take precedence over our short-term appetites. If we are unwilling to confront how each and every one of us is contributing to a worsening climate, then fulfilling the Paris Climate Agreement is a lost cause. So how damaging are these high-emission foods really? Raising food accounts for over a quarter of worldwide GHG emissions each year [3]. Livestock in particular composes nearly 15% of GHG emissions, more than all the cars, trains, ships, and airplanes of the worldwide transportation system combined [4]. These emissions are reflected in animal-based foods. According to Our World in Data, a research organization that addresses contemporary international issues, the top three GHG-emitting food sources are beef, lamb, and cheese. Beef is responsible for a staggering 60 kilogram CO2-equivalents (kg CO2-e) of GHGs per kg of product, lamb represents 24 kg CO2-e, and cheese for 21 kg CO2-e. Compare that to fruits and vegetables like apples, bananas, and peas, which all produce less than 1 kg CO2-e [3]. According to the Chatham House, global consumption of meat and dairy is expected to rise by 76% and 65%, respectively, by 2050 compared to the start of the century [4]. A collaboration between scientists from the University of Oxford; the University of Minnesota, St. Paul; the University of California, Santa Barbara; and Stanford University forecasts that food-related emissions alone will cause the world to eclipse the 1.5℃ threshold by 2050 and 2℃ by the end of the century [5]. With patterns like these, it’s no wonder that the IPCC recommends reducing meat consumption and has been influencing public opinion to that effect [6]. Cutting down on high-emission foods will be necessary in the fight against climate change. So why are certain foods more responsible for GHG emissions than others? Caring for farm animals requires intensive amounts of resources such as land. 78% of agricultural land is used for raising livestock [3]. The process of converting the land for grazing contributes heavily to GHG emissions. For instance, Brazil is the largest beef exporter on Earth, and cattle ranching has repurposed about 75% of the deforested area in the Amazon Rainforest into grasslands. Clearing trees leads to increased GHG emissions because the most common methods, burning and using machinery, are energy-demanding and release carbon dioxide [7]. Carlos Nobre, a Brazilian scientist speaking on behalf of the IPCC, stated that deforestation could eject over 50 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere within 30-50 years [6]. Additionally, clearing trees accelerates the problem, as plants absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. Transforming land into grazing pastures emits GHGs and weakens a powerful source of regulating them, posing a double threat towards combating climate change [7]. Once the land has been altered, farming facilitates the release of more GHGs. A quarter of crops are used for feed, meaning that the high-energy agricultural practices used for crops can be credited to meat production. These methods include the use of fertilizers, which are a major source of nitrous oxide, a GHG nearly 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Moreover, natural biological processes represent substantial contributors. Animal manure is another source of nitrous oxide, and enteric fermentation is the principal source of farm-produced methane, which is roughly 30 times as potent as carbon dioxide. Enteric fermentation releases gases when farm animals belch while digesting food. Currently, 39% of anthropogenic methane emissions and 65% of nitrous oxide emissions are attributed to the livestock industry, and atmospheric levels of these potent GHGs is anticipated to more than double by 2055 compared to 1995 [4,8]. Lessening our reliance on these animals for food would lessen their impact on the atmosphere. Which brings us to the question: How can we help? The World Resources Institute investigated diets that would diminish consumption of animal products in the United States. Unsurprisingly, switching to a vegetarian diet (while maintaining a constant caloric intake) greatly reduces agricultural per capita GHG emissions by over 50%. However, a radical shift like this would be difficult to achieve overnight for most Americans. Removing the most egregious offender from our plates may be more manageable. According to the same report, reducing beef consumption by 70% would lead to a 35% decrease in food-related GHG emissions. Even if Americans cut their beef consumption by just a third and fully replaced the loss of protein and calories with pork, chicken, or legumes, it would still result in at least a 13% drop in farming emissions [9]. Research has been consistent in other affluent nations, where meat consumption remains high compared to the international average. A systematic review of Western diets and GHG emissions examined 210 meat-reducing scenarios and found that 197 of them had lessened GHG emissions, with a median reduction of 22%. The vegan diet demonstrated the greatest decrease at 45%, with partially replacing meat anywhere from 7-12% [10]. Although meat-eating has been ingrained in Western culture for centuries, some have successfully transitioned to more sustainable diets. In an interview with PBS, vegan influencer Tiffany Stair described her transformation from a lifelong carnivore, revealing that she “ate meat three times a day, if not more.” She explained that altering diets on an individual basis can be done immediately: “You can make an impact right now, three times a day” [11]. While I am not encouraging anyone to go vegan (I haven’t!), focusing on just a few foods like beef can have significant outcomes. Humans will inevitably contribute to the greenhouse effect through what we eat, but controlling what we choose to eat represents a quick and straightforward path towards a reduced carbon footprint. Nevertheless, I recognize that we have a long way to go. I know that every package of ground beef I gloss over at the grocery store or every burger I forgo at a restaurant will likely end up in the cart of another shopper or the belly of a different diner. Retailers and restaurants must stock their inventories to meet the ever-increasing demands of hungry customers. Consumers tend to prioritize taste, price, and nutrition when it comes to their food choices, and industries continue to favor their business interests over environmental ones. It will require an enormous cultural shift and level of public pressure to incite lasting, societal change. I also do not want to fool anybody into thinking that lowering meat consumption and other high-emission foods in and of itself will be nearly enough. Over 75% of GHG emissions come from fossil fuels [3]. Strategies to reduce fossil fuel consumption, maximize energy efficiency, and convert to clean energy sources remain absolutely necessary. Despite facing an uphill battle, I urge everyone to pay attention to what we eat and take steps towards adopting a more sustainable diet. Recognizing the full impact of our indulgent lifestyles on the environment is long overdue. Collectively altering food consumption patterns is a direct method of beginning to limit our planet’s warming. Although one person alone cannot create a dent in food-related emissions, all of us together can create a consequential difference to fulfill the ideals of the Paris Climate Agreement and prevent our climate crisis from crossing a point of no return. Works Cited: [1] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Paris Agreement [Internet] [Cited 2020 Nov 21]. Available from: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement [2] Lindsey R, Dahlman L. Climate Change: Global Temperature [Internet] [Cited Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-temperature#:~:text=Change%20over%20time&text=According%20to%20the%20NOAA%202019,more%20than%20twice%20as%20great [3] Ritchie H, Roser M. Environmental impacts of food production [Internet] [Cited 2020 Nov 21]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food [4] Bailey R, Froggatt A, Wellesley L. Livestock - Climate Change’s Forgotten Sector: Global Public Opinion on Meat and Dairy Consumption [Internet] [Cited 22 Nov 2020]. Available from: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2014/12/livestock-climate-changes-forgotten-sector-global-public-opinion-meat-and-dairy-consumption [5] Clark M, Domingo N, Colgan K, Thakrar S, Tilman D, Lynch J, et. al. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2°C climate change targets. Science [Internet]. 2020 [Cited 23 Nov 2020]; 370(6517), 705-708. DOI: 10.1126/science.aba7357 [6] Schiermeier Q. Eat less meat: UN climate-change report calls for change to human diet. Nature [Internet]. 2019 [Cited 22 Nov 2020]; 572(7769), 291-292. DOI: 10.1038/d41586-019-02409-7 [7] Boucher D, Elias P, Lininger K, May-Tobin C, Roquemore S, Saxon E. The Root of the Problem: What’s Driving Tropical Deforestation Today? [Internet] [Cited 2020 Nov 23]. Available from: http://ice.ucdavis.edu/files/ice/UCS_RootoftheProblem_DriversofDeforestation_FullReport.pdf [8] Environmental Protection Agency. Understanding Global Warming Potentials [Internet] [Cited 2020 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/understanding-global-warming-potentials [9] Ranganathan J, Vennard D, Waite R, Dumas P, Lipinski B, Searchinger T, et al. Shifting Diets for a Sustainable Food Future [Internet] [Cited 2020 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.wri.org/publication/shifting-diets [10] Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJM, Smith P, Haines A. The Impacts of Dietary Change on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land Use, Water Use, and Health: A Systematic Review. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Nov 24]; 11(11). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165797 [11] Yu A. Should we stop eating meat to fight climate change? [Internet] [Cited 2020 Dec 4]. Available from: https://whyy.org/segments/should-we-stop-eating-meat-to-fight-climate-change/ [Image] Ritchie H, Roser M. Food: greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain [Internet] [Cited 2020 Nov 21]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |