|

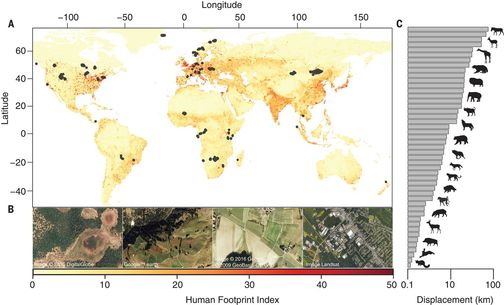

by Claire Bekker '21  One could argue that humans are the most successful invasive species on the planet. Since the first groups of Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa 70,000 years ago, we’ve colonized almost the entire globe, wrecking ecological havoc along the way. Over the last few centuries, humans have become increasingly dominant, modifying 50-70% of Earth’s land surface for our own use (1). According to Mark Williams, at the University of Leicester, “It’s not hubris to say this. Never before have animal and plants (and other organisms for that matter) been translocated on a global scale around the planet. Never before has one species dominated primary production in the manner that we do. Never before has one species remodeled the terrestrial biosphere so dramatically to serve its own ends” (2). And yet, our ecological impacts are only becoming more pronounced, in both obvious and subtle ways. Not only do human activities destroy habitats and decrease biodiversity but they also affect animals’ range, migration patterns, and overall vagility — their ability to move — through these fragmented habitats.  Researchers mapped the Human Footprint Index (HFI) globally and marked locations where terrestrial mammals were studied. They also included a bar graph with the average displacement for a number of the species studied. Researchers mapped the Human Footprint Index (HFI) globally and marked locations where terrestrial mammals were studied. They also included a bar graph with the average displacement for a number of the species studied. In a recent study published in Science, researchers examined the large-scale effects of human activity on mammalian movement. They used Global Positioning System (GPS) collars to track 803 individual animals from 57 diverse terrestrial mammalian species (spanning in size from pocket mice to elephants) around the world. To quantify the relative impact of human activities, the researchers gave each location a Human Footprint Index (HFI), a value based on numerous factors such as the extent of built environments, human population density, roads, and nighttime light pollution. Among all of the locations, HFI values ranged from 0 (no human influence) to 36 (greatest human influence). The researchers determined the median displacement (average range) and maximum displacement for each individual across different time-scales, ranging from one hour to ten days. Over longer time scales (>8 hours), animals in high HFI environments were significantly restricted in both their average and maximum range. On shorter time scales, the human footprint value did not have a significant effect; thus, human activity does not affect animals’ instantaneous speed but does affect their overall range (3). So why are animals restricted by human activity? Do animals intentionally change their behavior in areas with a high human footprint? Or rather, do migratory, long-range species tend not to live around areas with high HFI values? According to this study, both explanations are true. The restriction in animal vagility was a result of both animal behavioral changes and the species effect — animals with long-ranges tend to live in environments with less human impact. The researchers believe that animals are less likely to move in high human footprint environments for two reasons: first, there are barriers such as freeways that fragment their habitat and prevent movement, and second, more resources such as crops, water, and supplemental feeding are directly supplied by humans to the wildlife, allowing animals to stay localized (3). Animal vagility (mobility) has broader implications for global ecosystems as well. Their range of movement affects seed dispersal, food web dynamics, the spread of disease, and the exchange of individuals between different populations of the same species. With reduced vagility, migration patterns can be disrupted, populations may be cut off from one other, and plants cannot colonize new areas through seed dispersal. Large carnivorous mammals, who have the longest range, could lose access to food resources (3). In the vast project of human expansion, we often fail to recognize that we are encroaching on well-trodden paths and that the seemingly empty landscapes we explore are actually teeming with life. By developing networks of human civilization and resources, we are fracturing ecological ones. Now, more than ever, with the accelerating assault of both built environments and climate change on ecological systems, we need to reimagine our world as globalized not only from the human perspective, but also from an ecological perspective. Looking at a map of the world, we see the breadth of human connection expand overtime with more clusters of human existence being linked together by ships, planes, and most recently, the Internet. Yet beneath this anthropogenic atlas, an entirely different field of connections that holds together the whole biosphere is constantly shifting in response to our actions. We cannot let our focus on the first map obscure our view of the ecological one as we are only beginning to understand their interdependence and the inherent value of these biological connections. Works Cited

1 Comment

Angelaaa

3/22/2018 05:49:37 pm

"...we need to reimagine our world as globalized not only from the human perspective, but also from an ecological perspective." Amazing way to put it. Great article!!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |