A Review of The Pleasure of Finding Things Out by Matthew Lee '15

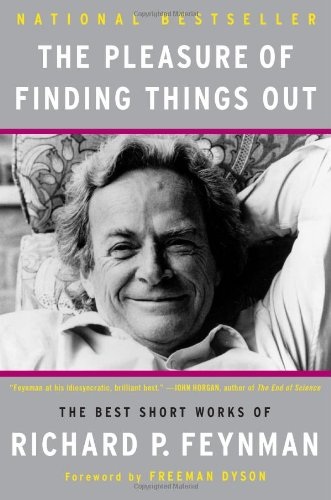

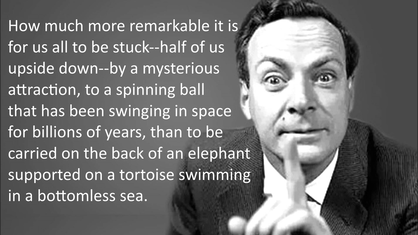

Even as Feynman grew up and learned more about the physical world, he would never forget his father’s lessons in observation and patience. Although his father was a salesman, not a career scientist, Feynman learned these principles of the scientific method and retained an insatiable curiosity for nature’s innumerable mysteries. These teachings would remain with him and inform his thinking and research, from cracking safes at Los Alamos to his mathematical formulations of quantum electrodynamics, for which he won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965 with Julian Schwinger and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga. Feynman recounts the above story and many more in The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, a collection that includes lectures, interview snippets, articles, his 1974 Caltech commencement address, and his report as a member of the commission investigating the Challenger disaster. Except for two lectures on what would inspire nanotechnology, all of the pieces are accessible to people without a deep background in science. Even if you are not an aspiring scientist, you can still learn a lot from Feynman and enjoy his conversational, sometimes rambling, gems of wisdom. Everything he says regarding science’s role in society, and society’s often passionate misunderstanding of science, is relevant today. If we look away from the science and look at the world around us, we find out something rather pitiful: that the environment that we live in is so actively, intensely unscientific…. What is all this nonsense about Mary Brody, or something? I don’t know, that was crazy stuff. There is always some crazy stuff…. There is faith-healing galore, all over…. You may laugh, but if you believe in the truth of the healing, then you are responsible to investigate it, to improve its efficiency and to make it satisfactory instead of cheating. (106-7) Since Feynman, the rift between people who believe in the validity of the scientific method and those who do not has grown dramatically as new technologies lead to new discoveries and a wider division in understanding at an ever-increasing rate. This division is especially evident in the debate between people who believe that the Judeo-Christian deity created the earth and its current palate of lifeforms in six days and those who believe in the sanctity of empirical evidence supporting the theory of evolution. Although today’s best science communicators such as Bill Nye continue to do their best in spreading the gospel of observation and experimentation, in 2013 the Pew Research Center found that a third of Americans do not believe in evolution. If Feynman were still around, he would probably step into the ring himself. The remark which I read somewhere, that science is all right so long as it doesn’t attack religion, was the clue that I needed to understand the problem. As long as it doesn’t attack religion it need not be paid attention to and nobody has to learn anything. So it can be cut off from modern society except for its applications, and thus be isolated. And then we have this terrible struggle to try to explain things to people who have no reason to want to know. But if they want to defend their own point of view, they will have to learn what yours is a little bit. So I suggest, maybe incorrectly and perhaps wrongly, that we are too polite. (111) Nevertheless, Feynman has no qualms with religion-inspired ethics or morals. After all, “there are good men who practice Christian ethics and who do not believe in the divinity of Christ” (254). However, Feynman admits that he doesn’t know if there is a way to reconcile the metaphysical aspects of religion with a scientist’s freedom to doubt. A scientist is never certain. We all know that. We know that all our statements are approximate statements with different degrees of certainty; that when a statement is made, the question is not whether it is true or false but rather how likely it is to be true or false. “Does God exist?” “When put in the questional form, how likely is it?” It makes such a terrifying transformation of the religious point of view, and that is why the religious point of view is unscientific. (111) Religion preserves a sense of awe by conceding that there are natural phenomena beyond the understanding of mere mortals. In contrast, Feynman argues that scientific progress inevitably leads to a greater sense of wonder and a more creative collective imagination precisely because scientific thinking gives us the tools to attempt to understand nature, which is always more awesome than our ancestors could have imagined. I would like not to underestimate the value of the worldview which is the result of scientific effort. We have been led to imagine all sorts of things infinitely more marvelous than the imaginings of poets and dreamers of the past. It shows that the imagination of nature is far, far greater than the imagination of man. For instance, how much more remarkable it is for us all to be stuck—half of us upside down—by a mysterious attraction, to a spinning ball that has been swinging in space for billions of years, than to be carried on the back of an elephant supported on a tortoise swimming in a bottomless sea. (143) Moreover, unscientific thinking stigmatizes doubt. Religion leaves little room for doubt and permits one to float on in ignorance; one either believes or does not. But Feynman argues that this dichotomy in belief and non-belief is incompatible for scientists, who “while they’re doing whatever they’re doing, [are] not so sure of themselves as others usually are” (200). Furthermore, Dr. Stuart Firestein at Columbia has argued that both drive and motivate scientific understanding in his 2013 TED Talk and book Ignorance: How it Drives Science, and Feynman agrees. When a scientist doesn’t know the answer to a problem, he is ignorant. When he has a hunch as to what the result is, he is uncertain. And when he is pretty darn sure of what the result is going to be, he is in some doubt. We have found it of paramount importance that in order to progress we must recognize the ignorance and leave room for doubt. Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty—some most unsure, some nearly sure, none absolutely certain. (146) Although this post has primarily focused on Feynman’s discussion of science and religion, The Pleasure of Finding Things Out encompasses many interesting topics, from working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos to criticizing a science textbook for first-graders. The book provides deep insights into the mind of one of mankind’s greatest and most entertaining thinkers. I highly recommend that not only aspiring physicists but anyone interested in enjoying the wisdom of one of history’s most brilliant minds check out this book. By the way, the title is the same as this 1981 interview with the BBC:

1 Comment

prof premraj pushpakaran

1/20/2018 12:38:40 am

prof premraj pushpakaran writes -- 2018 marks the 100th birth year of Julian Seymour Schwinger!!!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |