|

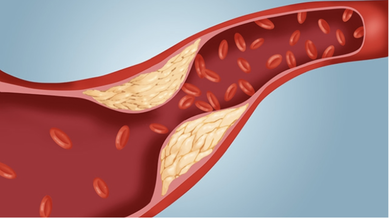

Written by: Jon Zhang ‘24 Edited by: Angelina Cho ‘24, Elizabeth Ding ‘24 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the #1 killer in the United States. According to the CDC, around 655,000 Americans die from CVD each year--one every 36 seconds [1]. Although CVD has no cure, lifestyle choices can lower its risk factors. A nutritional diet is fundamental towards physical and mental well-being, and foodies and health-conscious individuals alike must strike a balance between eating healthily and eating for pleasure. One dietary substance has garnered a notorious reputation amongst consumers and the medical community: cholesterol. In 1968, researchers first hypothesized that higher cholesterol consumption contributed to greater risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Afterward, the American Heart Association (AHA) began recommending Americans limit cholesterol consumption to 300 milligrams per day. However, these initial findings remained disputed throughout the scientific community, and demands for Americans to restrict cholesterol intake have become increasingly contested. Recent challenges to the original research prompted the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services to drop this daily recommendation in the 2015-20 Dietary Guidelines for Americans--further fueling the flames [2]. Cholesterol, a fat-like substance, is necessary for the composition of cell membranes and the synthesis of hormones. Diet-based cholesterol usually comes from animal sources like beef, chicken, and eggs. While these foods can constitute a balanced diet, the amount of cholesterol they contain may cause alarm. Chicken and beef contain 75 and 99 milligrams of cholesterol per 100 grams, respectively. Just one egg (50 grams) contains a whopping 186 milligrams, almost two-thirds of the AHA daily guidelines [2]. Although excellent sources of protein and other nutrients, does the cholesterol content mean that consumers should limit their consumption of these otherwise nutritious foods? Do the risks outweigh the benefits? Studies have begun to challenge this decades-long-held belief. Research supports that low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol is most directly associated with CVD. LDLs are proteins that transport cholesterol from the liver to other tissues through blood vessels, creating deposits known as plaques that clog vessels. As a result, scientists concluded that a high-cholesterol diet would increase LDL activity, leading to a spike in plaques deposited along blood vessels. However, recent investigations suggest the body can balance a cholesterol-rich diet with its own production of cholesterol. Cholesterol is synthesized in the liver through the mevalonate pathway, the rate of which is regulated by the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase. Dietary cholesterol intake inhibits the expression of this enzyme, decreasing internal cholesterol production to maintain homeostasis [2]. A high-cholesterol diet may be less responsible for plaque development than previously believed. So if dietary cholesterol is not the primary culprit, what is? The evidence relating saturated fats with CVD appears to be more conclusive. Animal trials show that saturated fats suppress the activity of LDL-receptors, most of which are on the liver. These receptors work to clear LDLs from plasma, so when saturated fat particles interfere with their function, more LDLs remain in the blood to form plaques [3]. However, not every evaluation is ready to let dietary cholesterol off the hook. A newly-published study in the Journal of the American Medical Association collected data from 29,615 participants between 1985-2016 and found that each additional 300 mg of cholesterol eaten per day was associated with a higher likelihood of incident CVD and mortality. While other sources suggest that the body maintains homeostasis between internal cholesterol production and external intake, this investigation argues that extreme and excessive cholesterol consumption disrupts this equilibrium and increases health risks [4]. Despite these findings seemingly vindicating dietary cholesterol, concerns will continue to exist in the minds of health-conscious shoppers and diners for the foreseeable future. There have been noble efforts to further our understanding of diet-based cholesterol. However, a lack of a consensus among scientists means shattering public belief in a 50-year-long convention will remain challenging. Though the debate is far from over, carnivores and fitness junkies may soon be able to breathe sighs of relief as they find it easier to walk the tightrope between nutrition and flavor. References:

[1] Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart Disease Facts [Internet] [Cited 2020 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm [2] Soliman GA. Dietary Cholesterol and the Lack of Evidence in Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Oct 27]; 10(6), 780. DOI: 10.3390/nu10060780 [3] Chiu S, Williams PT, Krauss RM. Effects of a very high saturated fat diet on LDL particles in adults with atherogenic dyslipidemia: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Nov 7]; 12(2), DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170664 [4] Zhong VW, Van Horn L, Cornelis MC, Wilkins JT, Ning H, Carnethon MR, et. al. Associations of Dietary Cholesterol or Egg Consumption With Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. JAMA [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Oct 28]; 321(11), 1081-1095. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.1572 [Image Citation] Sullenberger L. Your Cholesterol Level Does Not Matter [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.capitalcardiology.com/cholesterol-level-not-matter/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |