|

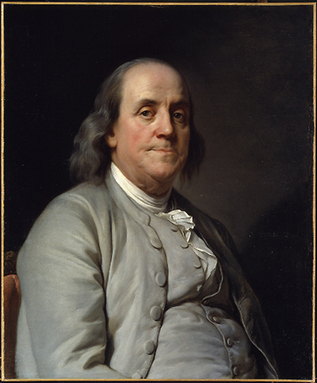

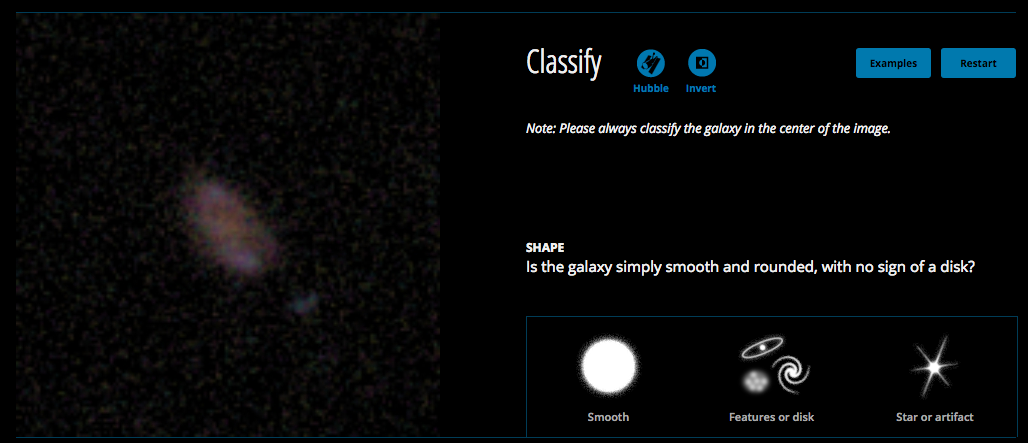

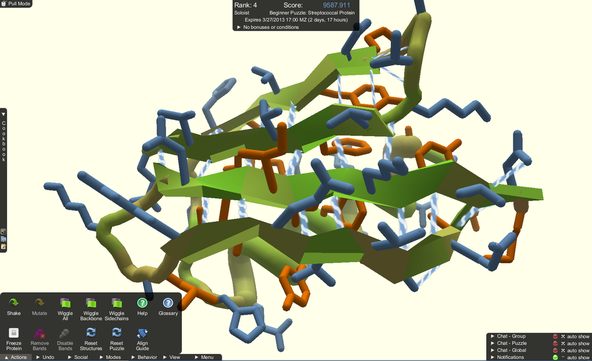

by Andrew Jones '16 Ben Franklin was a citizen scientist. A prodigious renaissance man, Franklin independently crafted a myriad of inventions and scientific experiments. While this maverick scientist was an integral portion history of scientific discovery, a new type of “citizen scientist” is emerging in the current information era. Non-experts can now contribute to large-scale research projects by gathering and analyzing small bits of data, all from the comfort of their own home. While citizen science is a currently an efficient mode of completing certain types of large-scale research projects, its benefits are temporary. Eventually, computational algorithms will improve in speed and flexibility and thereby overcome any inadequacies compared to humans. Citizen science can be divided into two types: one in which non-experts perform small scientific experiments, and another in which ordinary people make small contributions to a larger, well-established research initiative. While the first category was more prevalent at the dawn of modern science (think Isaac Newton and Ben Franklin), the second type has gained significant traction in the past couple decades and will be the focus of this article. Research initiatives that recruit citizen scientists typically involve large masses of data. Since sifting through these data would be extremely time-consuming for primary handful of researchers, these projects “hire” non-experts to perform simple tasks that contribute to the project. The tasks do not typically require a substantial level of knowledge in any given area of study. Instead, they recruit people’s cognitive resources to augment the study’s computational power. Galaxy Zoo is one project that has struggled with a shortage of personnel in the face of the data deluge. GZ’s website invites the general public to classify galaxies based on telescopic photographs taken from The Sloan Digital Sky Survey. After passing a short tutorial, people can begin classifying as many galaxies as they want. The project — which began in 2007 — has racked up over 50 million classifications from 150,000 different people.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |