|

by Sarah Blunt '17  Artist’s depiction of a black hole interacting gravitationally with a nearby star and emitting jets of x-ray radiation. [image via] Artist’s depiction of a black hole interacting gravitationally with a nearby star and emitting jets of x-ray radiation. [image via] Have you ever wondered what a black hole looks like? Do you imagine an insatiable dark pit traveling through space, devouring everything in its path? Or do you imagine a tear in the fabric of space and time, replete with wormholes to other universes and the lifeless bodies of intrepid astronauts? Fueled in part by imaginative portrayals such as these, black holes have become a favorite astronomical conversation topic. The phrase “so massive that not even light can escape” has captured the imaginations of middle schoolers and professors alike, and scientists are anxious to find out more about these invisible gravitational behemoths. What are black holes, and where do they come from? The most well-known types of black holes are the remnants of the explosive deaths of the most massive stars in the universe. At the ends of their lives, scientists theorize, these giant stars run out of the fuel that powers nuclear reactions in their cores, and they collapse under the sheer weight of their own gravity. These implosions force the stars to violently cast off their outer layers of gas and super-hot plasma, and then contract into the small (on the order of human size), extremely dense black holes we know and love [2]. Scientists have also discovered another type of black hole that they can’t quite explain theoretically. These objects, called supermassive black holes, have so much mass that they can’t have been formed by the gravitational collapse of even the biggest stars. The debate is still out, but some theorists think that these black holes may have formed just after the Big Bang: in this time of incredibly rapid expansion, there may have been enough energy to form these gravitational monsters [2].

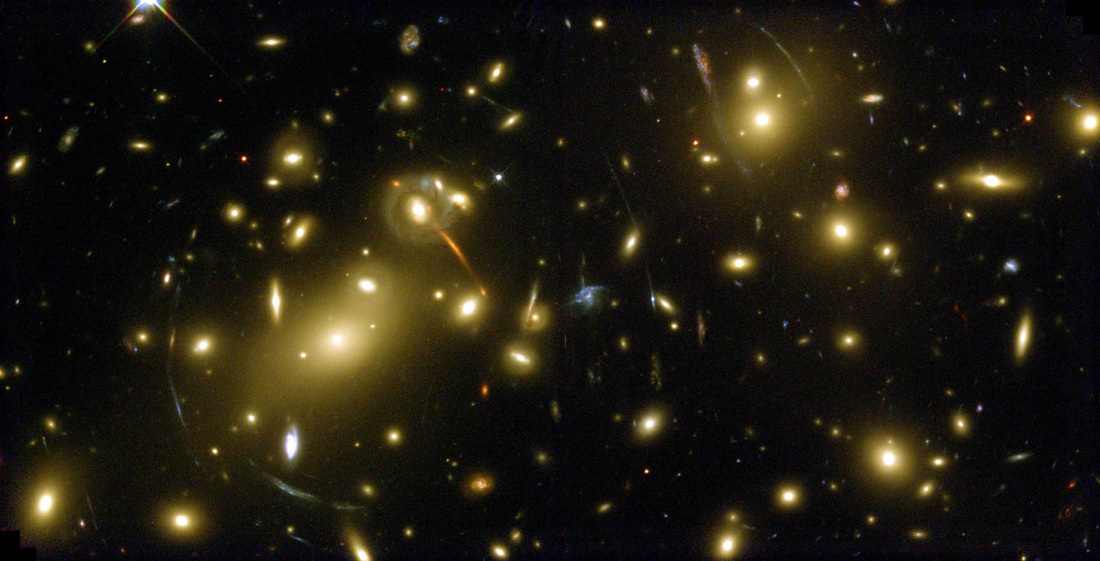

Hubble image of gravitational lensing around a massive galaxy cluster called Abell 2218. [image via]

So, if black holes are so massive that not even light can escape, how do we know where they are? Since black holes are invisible, the easiest way to find them is to look at their effects on objects in their vicinities. As a part of his General Theory of Relativity, Einstein predicted that the path of light beams would “bend” around massive objects. One sign that indicates the presence of a black hole to scientists is when light “bends” around seemingly empty space. If that “space” is massive enough to bend light, it could be a black hole [1]! Another way to confirm the presence of a black hole is to check if there are any astronomical objects acting strangely around the area. If an astronomer sees a star whose material looks as if it is being “sucked” into a dark region, the star might be interacting gravitationally with a nearby black hole. Finally, black holes with orbiting disks of cosmological junk often emit jets of super-hot material along their axes of rotation as a consequence of “overeating,” or sucking in too much material. Scientists see these emissions as x-rays, and can confirm the presence of a black hole if the x-ray jets are in perpendicular to the plane of the disk around the black hole [1]. Using these techniques, observational astrophysicists have been able to pinpoint the locations and characteristics of a number of black holes. However, the search is far from over! Are there any mid-sized black holes? What happens inside a black hole? How common are black holes in the universe? The hunt is on! References

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |