|

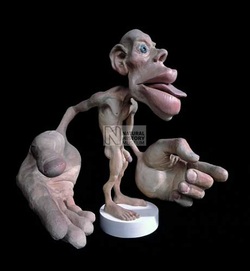

A Review of The Mystery Of The Mind By Wilder Penfield by Matthew Lee '15  "Hi, do you want a massage?" [image via] "Hi, do you want a massage?" [image via] Find this book in the Sci Li! Paperback: 152 pages Publisher: Princeton University (March 1978) ISBN-13: 978-0691023601 Anyone who has taken Neuro 1 will recognize the somatosensory homunculus, the funny looking guy with giant hands, puffy lips, and an emaciated body. The homunculus is based on a map of the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), and the size of each body part corresponds to the amount of brain that responds to a touch of that body part. Our brains devote the most processing power to understanding what our hands touch, so the homunculus’ hands are disproportionately large.  [image via] [image via] Dr. Wilder Penfield (1891-1976), an eminent Canadian neurosurgeon, provided the scientific evidence that evolved into the homunculus. He mapped out which parts of the brain are associated with which body parts by sticking an electrode into a patient’s brain, zapping it, and then asking the patient which part of their body had responded. Penfield also used electrical stimulation to investigate the relationship between the mind and the brain: does the mind arise from the brain, or are they separate entities? In The Mystery of the Mind, he considers the evidence he has collected from patients with epilepsy, who so graciously allowed him to poke and zap their brains.  If Penfield zaps the hand area in your brain, If Penfield zaps the hand area in your brain,your hand will feel something. [image via] Although the book was first published over three decades ago, it remains an important investigation of a question that has plagued mankind’s collective imagination for centuries. Penfield intended all sorts of people – “the clinician, the physiologist, the philosopher, and the interested layman, with apologies to each for the fact that I have not written for him separately” – to read this book, and he succeeds in making it accessible by defining technical terms simply and shunning pedantry. He begins by introducing fundamental ideas about brain function and structure (a brief review for neuro students) and then examines how consciousness is intricately linked to the brain. The very act of zapping the brain (specifically, the temporal lobe) appears to alter certain aspects of conscious awareness: "[A] mother told me she was suddenly aware, as my electrode touched the cortex, of being in her kitchen listening to the voice of her little boy who was playing outside in the yard. She was aware of the neighborhood noises, such as passing motor cars, that might mean danger to him." Furthermore, Penfield distinguishes between what it means to be truly conscious and what it means to simply “go through the motions.” For example, have you ever been walking or driving someplace new and then realized that you were on autopilot and missed a turn? Or perhaps you sit in lecture scribbling everything the professor has on the slides without taking a moment to consider what all of those words mean (never mind everything she says)? At all times, you are under the control of what Penfield calls the “automatic sensory-motor mechanism,” the part of your brain responsible for making your body do things . However, as the cases above illustrate, we are not always making use of the “highest brain mechanism,” which appears to account for mindfulness and active thought. Penfield describes patients who suffer from certain seizures that seem to disengage the mind and turn the person into an “automaton:” "One patient, whom I shall call A., was a serious student of the piano and subject to automatisms of the type called petit mal. He was apt to make a slight interruption in his practicing, which his mother recognized as the beginning of an “absence.” Then he would continue to play with considerable dexterity. If Patient C. was driving a car, he would continue to drive, although he might discover later that he had driven through one or more red lights." With clear commentary and plentiful anecdotes (including stories about the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Lev Landau, who suffered a stroke which rendered him immobile), Penfield leads us to a colossal, mind/brain-shattering climax. I’m not going to spoil it for you here, but let’s just say that after extensive testing, he concludes that “[t]here is no place in the cerebral cortex where electrical stimulation will cause a patient to believe or to decide.” Drawing upon his experiences as a neurosurgeon and scientist, he even discusses religion and death, and offers this advice to skeptical scientists struggling to understand faith: "[N]o scientist, by virtue of his science, has the right to pass judgment on the faiths by which men live and die. We can only set out the data about the brain, and present the physiological hypotheses that are relevant to what the mind does." The Mystery of the Mind is gripping, thought-provoking, and an absolute must-read for anyone who has ever asked the question, “Am I my brain?” For some budding neuroscientists and philosophers, the book may be a stepping stone into a career dedicated to research and reflection on how we are conscious and what it means to be so.

1 Comment

stravo lukos

7/12/2019 03:06:44 pm

I'm so confused. Back in the 70s, I read an article about holographic memory in which Pribram discarded Penfield's engrammatic memory because it was based mainly on work w/ epileptic brains which are different from the norm.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |