|

by Nari Lee '17

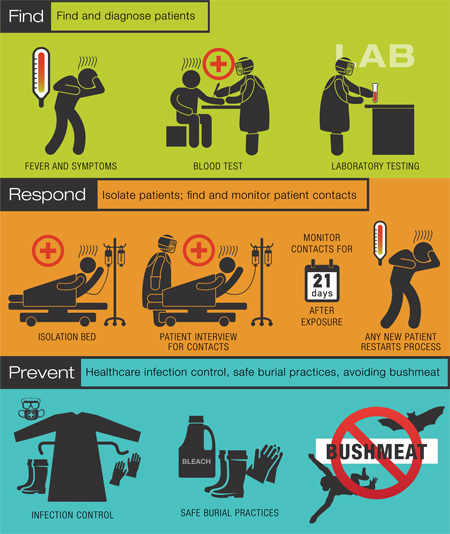

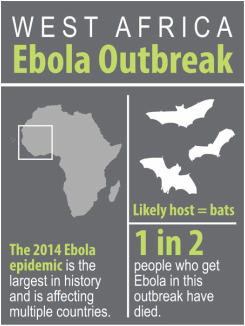

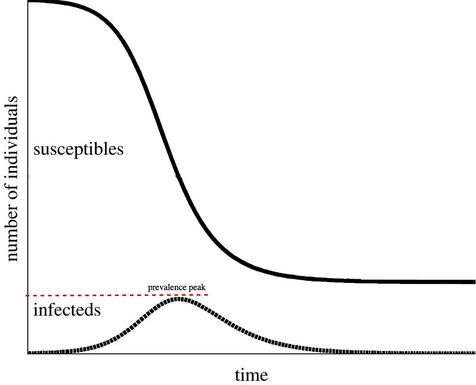

All Diseases are the SameI started off by asking Dr. Lurie what his research expertise in infectious disease has taught him that could be applied to the current Ebola epidemic. The answer was all about curves. Every epidemic typically has three phases: an initial stage of a few cases, followed by a period of rapid growth, then finally a decline and leveling off. When graphing the number of cases of the disease over time, we see a bell-like curve. The right side of that curve can plateau either higher than, lower than, or at the same level of cases as the initial prevalence. In that sense, I guess this so-called “epi-curve” resembles an energy diagram of a chemical reaction. Does that mean the Ebola epidemic will level off soon? The CDC has already declared that the epidemic has reached the stage of exponential growth. Dr. Lurie explained that the “doubling time,” the amount of time it takes for the number of cases to double, is now between 20-30 days for Ebola, whereas in stage one it was much longer. He pulled out a packet of papers from his cluttered desk and flipped to a diagram showing a generic epi-curve.  The epi-curve shows the three distinct phases of an epidemic by tracking the number of infected and the number susceptible to the disease.[image via] “At some point, there will be [a leveling-off]. See, what drives this part, this decline over here, is the amount of susceptible people. All of the people who are likely to become infected have already become infected, so you’ve got fewer susceptible people and that’s why it starts to go down.” He continued to say that we also don’t know how big this epidemic will get, our “prevalence peak.” The factors that drive any disease’s prevalence peak are the dynamics of disease, incubation period, level of infectiousness, and how many contacts those who are infected have. Now this is all if the disease were to run free in the absence of treatment. “Truth is, we’re not doing that anymore. We’re intervening. At some point, we’re going to see this curve going down, and it might be… months or years. We don’t really know. And it might be going down because we’re being successful intervening or it might be going down just because that’s the natural way epidemics do run when we’re running out of susceptibles.” The main intervention implemented globally has been quarantines of infected people. “That’s pretty much all that we’re doing,” Dr. Lurie said with a shrug, “and then we go to their contacts and watching them very carefully through this 21 day period, not necessarily quarantining them, but if they remain symptom free after 21 days, we don’t have to follow them anymore.” The 21-day period he mentioned is the outer limit of the number of days during which people show symptoms if they have been infected with Ebola — most people show symptoms within 8-10 days, but health agencies watch for 21 to be safe. The Age-Old problems of money and discriminationOk, so we quarantine those who are infected, and follow their contacts who may have been exposed. Why can’t we then save resources and test for the Ebola virus in the contacts’ blood right off the bat? According to Dr. Lurie, “an Ebola positive test doesn’t turn up until you start to have symptoms.”

Why in the world did we wait until there were more cases and the need for more time, money, and resources? Dr. Lurie named a few reasons: 1) Ebola wasn’t on the international radar. In the six months before we endlessly started hearing about Ebola, the epidemic was in the first stage and “people could think about it as a problem for them and not for us [emphasis added].” 2) Health agencies have had their budgets cut so much in the past few decades that they no longer have the capacity to respond to something like Ebola. At that time, Ebola was simply “a potentially emerging problem.” Agencies like the CDC and WHO had to prioritize and allocate their resources to diseases like HIV or TB where high numbers of people are known to be infected. 3) Because of these budget cuts, private donors and organizations have begun to fill in some financial gaps. As a result, health agencies’ interests are now tied to those of the donors. “If Bill Gates is interested in vaccines, there’s plenty of money for vaccines. . . there was nobody around who was saying that we really have to plan for Ebola and . . . [gave enough money] before the epidemic so that we could have drugs that would be ready.” These economic motivations and biases are why it took health agencies so long to respond, and though they are responding, they’re not very successful because they’re just so late in the game. I probed a little further on the reason Dr. Lurie gave for why Ebola wasn’t on the international radar—the discriminatory thought that Ebola was “their” disease and not “ours.” He cautiously stated, “I don’t think it’s any question that it happened amongst people of dark skin in countries that have the fewest resources. If it started in this country, there would have been a lot to throw at it. There’s no two ways about that.” Dr. Lurie added that, “Thinking of it as 'their problem' is a racist attitude… We all live in the same place and it’s only 12 hours in a plane to West Africa.” Don't trust the numbers

Another number that should be taken with a grain of salt is the case-fatality rate (CFR) for Ebola. The CFR is calculated by dividing the number of people who died of disease by the total number of people infected. On the WHO website, it says that the CFR for Ebola is now around 50% with about 5,000 dead and 10,000 cases. Dr. Lurie stressed that for each of those 5,000 cases remaining alive, we don’t know if they are going to die or will be cured. Some of them simply haven’t gone through the natural course of the disease yet. However, the given CFR assumes that the infected individuals who have not yet died will survive when actually a large proportion of them will die. When we go back and calculate the CFR after the epidemic is over, Dr. Lurie predicts that the CFR will be closer to 70% if the epidemic remains at the same pace. Other cool peopleThere was a lot to take away from my conversation with Dr. Lurie, and I am so glad to have had the opportunity to learn all of this from him.

If you’d like to see what it’s like up at the front line of defense, check out Dr. Tim Flanigan’s blog. Dr. Flanigan is one of Brown’s very own infectious disease specialists who is helping to fight the Ebola epidemic in Liberia. You can also learn more through Dr. Adam Levine, an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at Brown’s medical school. He was recently on CNN to discuss Ebola and also writes dispatches from his Ebola Treatment Unit in Liberia for the Huffington Post.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |