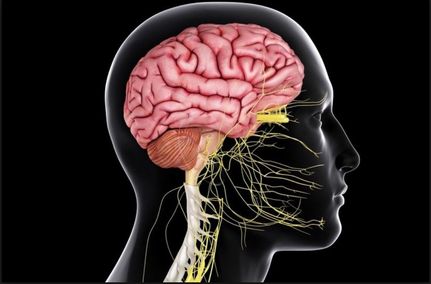

Image of the Central Nervous System. https://www.thoughtco.com/central-nervous-system-373578 Image of the Central Nervous System. https://www.thoughtco.com/central-nervous-system-373578 By Emily Rehmet, '20 For years, the American Psychological Association has classified eating disorders into a discrete category on its own, a direct byproduct of patients having doubts about their body size and image. However, a recent study suggests that bulimia nervosa may be connected to something deeper… a vehicle for people to escape from self-critical thoughts. New research has shown that rather than simply having an obsession with food, women with this disorder have decreased blood flow to a brain area associated with self reflection and self worth. What is this newly discovered brain area that could be causing this you may ask? A region called the precuneus [1].

1 Comment

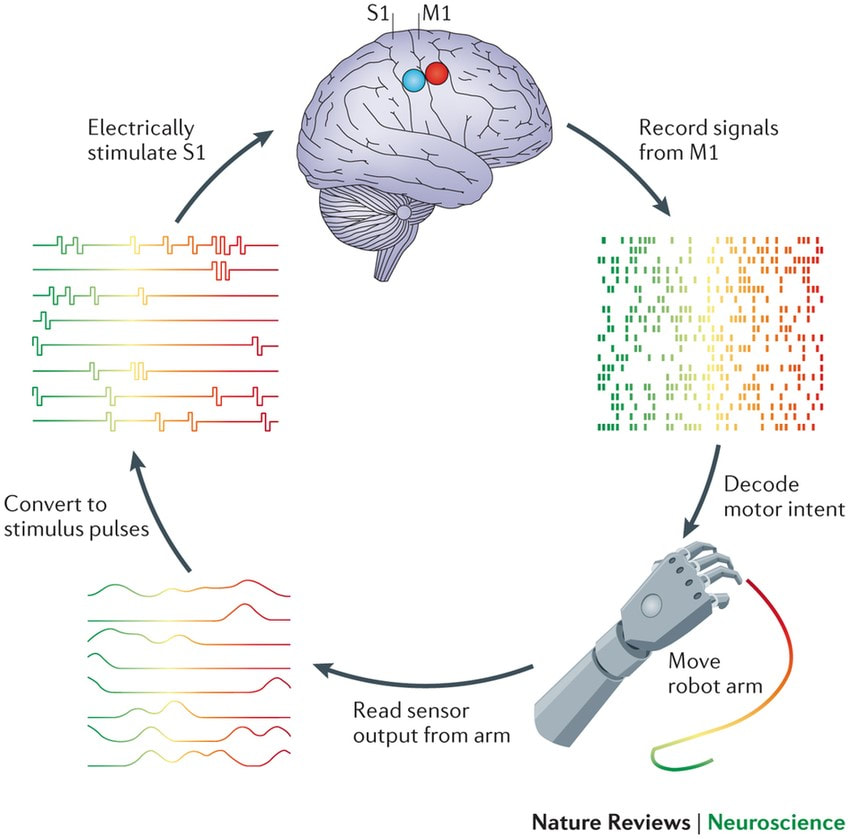

By Jess Sevetson Figure courtesy of Sliman J Bensmaia & Lee E Miller. “Restoring sensorimotor function through intracortical interfaces: progress and looming challenges” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2014 May The term “mind reading” usually suggests the ability to read out someone’s thoughts like an audiobook. While there has been some progress on that front recently, another application of these technologies is the ability to operate advanced prostheses. by Rahul Jayaram '21  Human brain scan shows visible evidence of lymphatic vessels. (Credit: Reich Lab, NIH/NINDS) Human brain scan shows visible evidence of lymphatic vessels. (Credit: Reich Lab, NIH/NINDS) Of all the organs in the body, the brain is undoubtedly one of the most enigmatic. Today, there is still so much that is unknown in the field of neuroscience, and one can never predict when new discoveries will be made. The mechanisms behind how our brain maintains cellular health were always believed to be in a separate realm from the rest of our body. Just days ago, scientists discovered a game-changing facet about how the brain functions that has the potential to change the future of neuroscience research. By Misbah Noorani '17 Here at Brown, “consciousness” is an oft-touted concept. It's ontologized by philosophers, attempted by artificial intelligence researchers, black-boxed by cognitive scientists, and reduced to its neural correlates by neuroscientists. Step into the physics department, though, and you won’t hear a whisper of the Hard Problem; at least, not in the bubble of academia. Now try typing “consciousness” into your Google or YouTube search bar, and it’s a different story entirely.

by Jennifer Maccani, PhD  The painter Wassily Kandinsky was a well-known synesthete who saw music. [image via] If you’re a fan of classical music, you’ve likely spent a rhapsodic hour daydreaming to the lilting melodies of Beethoven’s sixth symphony, the “Pastoral,” so-named because the music is said to evoke images in the mind’s eye of rolling fields, fluttering streams, and tinkling birdsong. Yet, for roughly 0.05-1% of the population (1), Beethoven’s masterpieces can evoke far different—and far more vivid—imagery. For these people, music and/or other sensory stimuli trigger immediate perceptions that feel as real as the music itself, often in the form of color and shape (2, 3). These people were born with what some might consider a real-life superpower, a condition called synesthesia. The most common type is grapheme-color synesthesia, in which letters or numbers elicit colors in the mind’s eye. For synesthetes, these colors are an essential part of the letters or numbers themselves, almost a part of their essence or identity (4). However, over 60 types of synesthesia have been identified in the population; in fact, there may be 150 or more distinct types (5). Music can evoke spatial sensations, shapes or colors (6-8); words can taste sour or sweet (9); voices can look like grey smoke or dry, cracked soil (9, 10); or the sound of a car horn can smell like strawberries (11). Even the personalities of one’s family and friends can have their own distinct colors (12). Individuals may have only one type, or several, and some of them—such as voice-color and personality-color synesthesia—are rarer than others.

by Jennifer Maccani, PhD This article is part of the "Emerging Biotechnology" series. Is telepathic communication possible? As outlandish as it might sound, this question drove Hans Berger to investigate the electrochemical basis of brain activity—a line of research that eventually led to the invention of the electroencephalogram, or EEG, which measures the brain’s electrical impulses via electrodes attached to a person’s scalp (1). We can find clues as to what led Berger down this path by studying his early life. Berger was born in 1873 in Coburg, Germany. His diaries reveal that he was an introspective and solitary young man. After a short stint at the University of Berlin, Berger turned away from early leanings toward a career in astronomy and enlisted for military service in Würzburg, where a near-death experience radically altered his aspirations. One morning in 1892, Berger’s horse became spooked during an exercise with his artillery unit. Berger was thrown to the ground and into the path of an oncoming artillery cannon’s wheel. Although the cannon stopped just short of crushing him, Berger was thoroughly rattled. When his family sent him a telegram that evening inquiring about his wellbeing, they revealed that his sister had that very morning feared that something had happened to her brother. Berger became convinced that “it was a case of spontaneous telepathy in which at a time of mortal danger I transmitted my thoughts” (2). It may have been this very experience that led him, upon the completion of his military service, to attend Jena University in Jena, Germany and pursue his research on the electrical activity of the brain (2-4).  "In Germany I am not so famous." [image via] by Georgia Bancheri '15 Ladies and gents, have you ever wondered what drinking does to the brain, besides make you look like one class act of a gent (picture provided for those who’d like to emulate such)? I mean, I’m sure that’s what you’re all talking about come Saturday night when you’ve got a sex on the beach in your hand and you’re mmms mmmsing on the dance floor. (Gents, I know that’s your preferred drink. Don’t be ashamed.) Well, copious drinking can cause a neurological disease called Korsakoff’s Syndrome. I’m talking ‘bout more than your average beer-bellied frat boy drinking. (Frat boys, if you’re reading, don’t fret too much…) Anyhoo, the main symptom of Korsakoff’s is confabulation--in lay-man’s terms, flat-out lying--but, get this, the person whole-heartedly believes their lies.

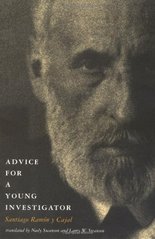

A Review of Advice For A Young Investigator by Santiago Ramón y Cajal (Translated by Neely Swanson & Larry W. Swanson) by Matthew Lee '15  [image via] [image via] Find this book in the Sci Li! Or read the full text online! Paperback: 176 pages Publisher: Bradford Books, The MIT Press (1999) ISBN-13: 978-0262681506 In 1906, two rival neuroscientists shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine: Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Golgi firmly believed in the reticular theory, that the brain consisted of a single network. In contrast, Cajal contended that the brain actually consisted of discrete cells. As it turns out, Cajal was right. Cajal (1852-1934), who hailed from Spain, spent years at a microscope and painstakingly drew neurons. After all, it would be quite some time before we would be able to take pictures of cells. His descriptions and depictions of the nervous system are so detailed that they serve as a foundation for modern neuroanatomy.  A section of a sparrow's optic tectum. [image via] Well into his career but a decade before winning the Nobel Prize, Cajal wrote Advice for a Young Investigator, a short guide rife with humor, anecdotes, and timeless wisdom for students aspiring to become great scientists. The book was so popular three more editions were published over the next twenty years. In 1999, Neely Swanson and Dr. Larry W. Swanson released a translation that preserves Cajal’s straightforward, yet eloquent, prose.

|